Firstly. A big thank you to all of you for putting up with the server problems that accompanied the arrival of my first blog essay, or blessay as I quite horribly prefer to call it. I thank you all for your suggestions, tips, links and comments. I can’t reply to all the points raised, but I will say that (A) the Nokia E series iSync plugin just simply doesn’t work for me, nor do any third party offerings. “Unexpected error”. I shall wait till Missing Sync come up with their solution which is due soon and (B) no, I don’t want my iPhone hacked or cracked, thanks very much for the offer. We may return to the geeky side of my life a little later.

This blessay, while entirely different in other respects, is also unaccountably and inexcusably prolix. Sorry about that, I don’t seem to be able to keep things brief. So my advice is that you read it in bits. Or print it out and save it for a rainy day or a recalcitrant motion.

I will try to produce more traditional ‘dear diary’ style down-and-dirty blogs if that’s what you would prefer, but I advise you to be prepared to expect a mixture of the long and the short.

My subject this week is Fame….

Let Fame, that all hunt after in their lives, Live registered upon our brazen tombs…

I have been pondering this business of fame since I was young enough to know Valerie Singleton from the Queen (for Americans and other non-Britons I should explain: one is a remote, god-like, autocratic woman endowed with powerful charismatic charm and the other is a constitutional monarch recently played on screen by Helen Mirren).

Some questions will be addressed in the following blessay:

· Is fame really something that “all hunt after in their lives”? · Whose fault is fame? · Can we postulate a kind of fame meme? · What’s it like being famous, Stephen? · What are the bad things about being famous?

The quotation I opened with is so firmly branded on my memory that I have no need to check it: it’s from the beginning of Love’s Labour’s Lost. When I was in a student production nearly 30 years ago Hugh Laurie played the King of Navarre and was incapable of delivering those opening lines without giggling; what set him off was catching the eye of Paul Schlesinger, who played Berowne. This happens on stage; I remember having a similar problem with John Gordon Sinclair – the only way we could get through some scenes of The Common Pursuit was by looking away from each other. It’s a chemical thing, like a kind of (mostly) benign allergy, impossible to explain or predict. Anyway, Hugh Laurie had the affliction big time with Paul Schlesinger. So much so that the harassed director, Brigid Larmour, was forced to get the entire company of attendant lords to intone the opening speech tutti, as a kind of chant or oath, to draw attention away from the corpsing. Brigid Larmour is now artistic director of the Watford Theatre, Paul Schlesinger is the head of BBC Radio Entertainment and Hugh Laurie has disappeared into oblivion. How the whirligig of time brings in its revenges. I played Don Armado incidentally, a character with the best description in any of the Shakespearean dramatic personae: he is “Don Armado, a fantastical Spaniard”. Only I was Don Armado, a fantastical Mexican because … oh, it’s another story altogether.

Intro For the duration of much of what follows it might be a good idea if you cast yourself as famous. Much of success in life comes from being able to put yourself in the shoes of another: in the shoes of a prince or a pauper, a dictator or a dick-head, a burgomaster or a burger-flipper, regardless of degree, status or esteem, it’s what imagination means – the ability to penetrate the consciousness and experience of another. It’s perhaps the defining characteristic of the artist. So, rather than look at fame from the outside which we can all do (only members of a royal family are born famous after all) try in the following paragraphs to look at fame from the inside. I’m not suggesting this because I think famous people need especial understanding or sympathy, it’s just that I suspect much of what’s written below will make more sense that way. Besides, isn’t it the best way to read anything? Only resentful bores and bitter egoists see everything from their own point of view, surely?

Fame. It’s an embarrassing thing to talk about, for all that it is a national/global obsession. It is one of the few apparently desirable human qualities that … no, what am I talking about … it is not a quality. It is not like courage, mercy, kindness, strength, beauty or patience; or laziness, dishonesty, greed or cruelty for that matter. What is different about fame, I was going to say, is that it is so contingent. If you are tolerant or strong or wise, you are tolerant and strong and wise wherever you are on the planet that day. You don’t become bigoted, feeble and dim-witted the moment you cross a continent. Famous people however, can become entirely unknown the second they leave their homeland. Only the World Famous are famous everywhere, and there are precious few of them. They used to claim Mohammed Ali was about as well-known as a human could be, the same was said of Charlie Chaplin and Elvis. Who now? Osama bin Laden? Michael Jackson? Robbie Williams can walk around Los Angeles without being recognised and they say Johnny Carson was so surprised/irked/mortified at going unremarked in London whenever he showed up, as he did regularly for Wimbledon Fortnight, that he arranged for British TV to carry his Tonight Show at a reduced rate. Martha Stewart can travel by Tube unspotted, but not by Subway. And so on. As for myself, well, I mean next to nothing in Italy, but seem to strike a chord in Russia. Don’t ask.

Fame has this unusual property. It exists only in the mind of others. It is not an intrinsic characteristic, feature or achievement. Fame is wholly an exterior construct and yet, for all that it is defined by other people’s knowledge of a given person, they cannot dismantle or deactivate the fame that their knowledge engenders. What an ugly sentence. I mean this. We cannot, however much we may want to, make someone unfamous. We can make them infamous, unfashionable, notorious, despised or derided but the more we do so the more we actually increase their level of fame. Fame is a function of memory. I can’t impel you to forget Adam Sandler, for example, any more than I can instruct you to forget Jack the Ripper or the Jolly Green Giant. Indeed, as I’ve suggested, to urge someone to forget is worse than useless. It’s like the well-known procedure of telling someone not to think of something specific and odd, a yellow panda, for example. Go on, do not think of a yellow panda. There, the image of such a being is now in your head. Fame is a great bouncy castle that we have all blown up to its present state by breathing the names of the famous. Simply in mentioning ‘Adam Sandler’ I have inflated his fame by a cubic millimetre. It will only deflate, over time, if his name is never uttered. Given his slate of disgustingly maudlin films over the last five years (with the exception of the wonderful Punch Drunk Love), I can’t help feeling that wouldn’t be a bad idea, but this is an entirely separate argument.

For fame is not the same as reputation. Fame can outstrip reputation, but reputation cannot outstrip fame. For example, while Kipling’s fame has been great since his death, his reputation has wavered, one minute down in the cellar, the next back up to almost the height it attained in his lifetime. Ditto, more or less at random, the pre-Raphaelites, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Bobby Darin. W. B. Yeats is better known these days than Dornford Yates, and that’s likely to remain true till the crack of doom: two generations ago for every person who had heard of W. B. there were a hundred who knew and read Dornford. Am I alone in liking both?

All of which leads me to this obvious point. It is no good everyone repeating that tiresome cliché about x, y and z ‘only being famous for being famous’ – their fame exists in our heads and it is therefore our fault, not theirs, if fault there is. I can’t blame Jade Goody for the fact that I know her name. Many famous people may well be guilty of being ambitious for fame, for ‘hunting after it all their lives’ as in the quotation above, but while I could be guilty of wanting everyone in Britain to send me ten pounds such an ambition is useless unless others are foolish enough to realise it for me. It is our curiosity, admiration, idolatry, envy, rage, resentment or obsession that privileges the famous with their fame and the only way we can take it away from them is by forgetting. Which is hard. And it’s no good saying: “it’s not my fault Abi Titmus is famous … it’s other people who have made her so” – the very act of uttering that sentence has spread the infection, has transmitted the fame meme. Yes the media institutions, the newspapers, television and indeed internet have a part to play as pipelines, but the energy that drives the fame along those pipelines derives more from the receiver than the transmitter, it is more suck than blow.

The Pheme. This would combine a resurrection of the Greek notion of Pheme, the spirit or embodiment of fame, (Roman equivalent Fama) with the meme proposed by Richard Dawkins (do visit his site – fine place, intellectually stimulating but non-combative and you can buy a cool atheist A t-shirt). Let the pheme ƒ be the gene of celebrity, the base unit of fame; its only function is to replicate itself by planting the awareness of a given famous person, x, into the host minds of the masses, m. The pheme of x, ƒ(x) does not demand that you like x, respect them, admire them or even know much about them, only that you are conscious of them enough to pass on the pheme in some manner. In fact, I would suggest that a negative attitude to x actually transmits the pheme more powerfully. The fame of someone despised or caught with their hand in the till, a straw up their nose or their knob up an inappropriate fleshly passage transmits more rapidly than the fame of one who has invented something useful or created something beautiful. Interestingly, the collective unconscious of the Greeks (characteristically as wise, poetic and insightful as their conscious philosophy) personifies Pheme as a many-tongued gossip, rather like Rumour in 16th and 17th century English allegories. For a pheme is transmitted by speech, or more properly, by utterance, written or spoken. I’ll leave the mathematical modelling and notation to cleverer heads than mine, but I don’t doubt that some sort of descriptive formula can be produced which will allow us to see how phemes work over time and across populations.

More characteristics of Fame. A good metaphor for fame is the magnifying glass. It makes larger (which is what magnify means) exposing flaws as well as qualities. The blackheads and dirty pores are there for all to see. Like a magnifying glass fame can distort, it can invert and it can (with the glare of publicity behind it) focus the light into a terrible heat that burns the subject until they shrivel into nothing.

In some professions fame is a by-product, an incidental, a “way of keeping score”. If you are a brilliant cricketer, one of the best in the world, then as many as two billion people might know who you are. Even more if you are a successful footballer. A maximum of a quarter of a billion will know who you are if you are a successful American footballer, but at least 5 billion will know you if you are an American footballer accused of murdering your wife and her lover. The OJ pheme buried itself deep in all of us and will, one suspects, remain in circulation for a long time. But then society thought the same of the Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle scandal which is now, if not an obscure footnote, certainly far from being the cause celebre of the century despite its seismic notoriety at the time.

If you write books, sing songs, act in films, read the news etc etc, fame will come as a consequence of popular success in those fields as surely as a cough will come to a coalminer. If you murder people on a sufficiently impressive scale, either as an individual or a political leader, your name will get around that way too. It goes without saying that fame has nothing to do with the quality of your achievement. Dan Thingy who wrote the Leonardo Code or whatever it was called, is fairly well known now but will be as unheard of as Rafael Sabatini or James Hilton in fifty years time (though they deserve more fame than he ever did). Tim Berners-Lee is possibly less well known than Bernard Lee (M in the early Bond movies), but in the future the reverse will be true. And so on.

Dan Whatsit and his preposterously awful Leonardo book are actually relevant to our theme. I usually last longer with any best-selling novel, however pathetic, than I did with his. But in his case I knew from the very first word that this was a writer of absolutely zero interest, insight, wit, understanding or ability. A blunderer of monumental incompetence. The first word, can you credit it, is ‘renowned’. ‘Renowned symbologist Henry Titfeather ….’ or something equally drivelling, that’s how this dreadful book opens. How do you begin to explain to someone that you just don’t start a fictional story by telling your readers that your character is ‘renowned’? You show it, you don’t tell it.

Lord Reith, founder of the BBC, legendarily fired off an angry memo to his staff after a broadcast in which someone or other was described as “the famous lawyer”. The memo went like this: ‘The word FAMOUS. If a person is famous it is superfluous to point out the fact, if they are not then it is a lie. The word is not to be used within the BBC.’ Way to tell them, Scottish guy.

Of course those for whom money is important will tell me that Dan Doodah is ‘laughing all the way to the bank’ and that his sales are all the approbation he needs. Well those who think money is any more reliable than fame as an index of worth are already beyond help. Eat shit, a trillion flies can’t be wrong. Or as someone once said, (Dorothy Parker if you believe the online quotation pages, which I don’t – I mean do they ever show sources or give chapter and verse?) : ‘If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the kind of people he gives it to.’ Of course Dan Whosit is a success, of course he’s reasonably famous at the moment. I don’t begrudge him a cent of his money or a breath of his ‘renown’. The awfulness of his book is only of interest because it is so successful, precisely because it has become so ‘renowned’. There are hundreds of thousands of books a year published that are bad, it says nothing about the authors. The success of Leonard’s Code is all about and only about the mass of people who bought it and thought it had a vestige of quality or authenticity and so caused the spread of its pheme. This is true of all fame: it’s not about the famous, it’s about those who make them famous and why. ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in our selves…’ Cassius’s observation works with the modern meaning of ‘star’ too.

Fame has this in its favour: you can’t fake it and it’s absolutely no good arguing over its existence, it’s as provable as anything can be. We could wrangle over whether or not Dan Howdoyoudo can write, but we can’t argue about whether or not he’s famous. Mind you, he can’t be that famous if I can’t recall his surname … Brown! Damn, I suddenly remembered. I wasn’t going to look it up but had planned to rely on it either springing into my head or not and, annoyingly, it just has (or “it just did”, as Americans would say). He is, or rather the phenomenon of his dreadful book is, certainly famous. Whether or not I have the right to append the adjective “dreadful” to his work is however a matter for debate, ultimately a question of taste (ie, if you have taste you agree with me, if you haven’t you don’t – no but shush). Dan Brown is famous, but not significant. Tim Berners-Lee is significant, but not famous.

Mind you, interesting how cold Dan Brown has become recently. The ‘phenomenon’ has dried up and already feels as embarrassingly dated as Bri Nylon shirts or backwards baseball caps, but without the kitsch retro appeal.

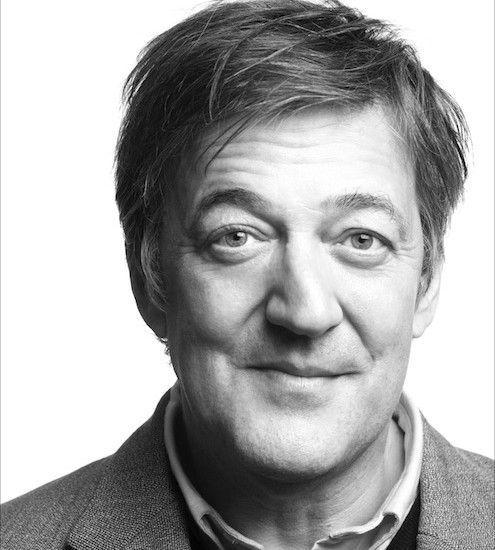

My Fame Alright, I’ve hedged enough. What does fame really mean to the famous? I am pretty well-known in my own country, I can’t deny that. It would be a false modesty weird enough to count as vanity to pretend otherwise. I get stopped on the street, I get (occasionally) hounded by photographers, I get letters from strangers asking for money, sex, advice, approval, time and so on. Journalists with nothing better to do write descriptions of my personality or offer glancing mentions of me. People who have never met me know that they loathe me, or that they like me. I am asked to be patron of this charity and to be on the board of that good cause and so on. I can get a table at the Ivy restaurant and tickets for premieres and parties. A medium ranking sleb. Not A list, but not Z either. I’ve been in this position for the best part of a quarter of a century.

Is it fun? Or, as student journalists always ask, what’s it like? ‘What’s it like working with Natalie Portman, what’s it like doing QI, what’s it like being famous?’ I don’t know what it is like. What is being English like? What is wearing a hat like? What’s eating Thai red curry like? I don’t believe that I can answer any question formulated that way. So, student journalists, tyro profilers and rooky reporters out there, seriously, quite seriously never ask a ‘what’s it like’ question, it instantly reveals your crapness. I used to try getting surreal when asked the question and say things like ‘being famous is like wearing blue pyjamas at the opera. It’s like kissing Neil Young, but only on Wednesdays. It’s like a silver disc gummed to the ear of a wolverine. It’s like licking crumbs from the belly of a waitress called Eileen. It’s like lemon polenta cake but slightly wider. It’s like moonrise on the planet Posker.’ I mean honestly. What’s it like?? Stop it at once.

No, but really Stephen, what is it like, being famous? Go on.

Oh, very well then. I can only tell you what being famous as Stephen Fry is ‘like’, of course. I suppose there must be some elements to the experience that I have in common with other famous people, but in the end being famous as Stephen Fry is not the same as being famous as Carl Sagan or David Furnish or Vernon Kaye.

I’ll start with a story that illustrates exactly one aspect of that point. 15 or so years ago I was filming a TV drama called Stalag Luft in Harrogate with Nicholas Lyndhurst. After a couple of nights sampling the hotel’s room service menu we decided to totter into town and try our luck in an Indian restaurant. We were spotted by a group of young Harro … young Harrogaters? Harrovians won’t do it. Whatever, a sample of Harrogate youth button-holed us. They hailed Nicholas in a strange blend of North Yorkshire and attempted South London, punching him playfully but quite forcefully on the arm and saying ‘Come on Rodney, you fucking plonker, give us your autograph, you daft cunt.’ They roughhoused him like this as he patiently signed, and then they turned to me, all but doffing their caps, and asked in a very polite tone, ‘Excuse me, Mr Fry, but can we have your autograph too?’ Walking away from this encounter Lyndhurst said in an aggrieved tone as he rubbed his bruised upper arm: ‘What the hell was that about? I get called a cunt and violently punched and you get “excuse me Mr Fry”???’. ‘Ah,’ I said, ‘thing is, you play everyone’s favourite younger brother and so they treat you like a younger brother, while I play generals and lawyers and bishops and they treat me accordingly.’ ‘Right, that’s it,’ said Nick, ‘from now on it’s bishops and generals only.’

So, being famous-as-me has its advantages. I am perceived (and whether this might be right or wrong, accurate or inaccurate, is for the purposes of our discussion neither here not there) as being authoritative, patrician, benign, knowledgeable etc etc, whatever, whatever. Therefore I am treated rather differently to those who are adjudged to have other qualities. On the one hand I am not slapped on the back or punched in the arm much, on the other I am not an object of sexual thrill or a youthful role-model in the way a footballer, musician or soap star might be.

One advantage I have over some is that my fame came pretty slowly. I left university in 1981 and over the next three or four years did a bit of this and a bit of that – a TV series called Alfresco for Granada that was not exactly a major hit, a stage production of an Alan Bennett play and the second series of Blackadder followed without setting the world on fire. By about 1986 I was starting to get used to being stopped in the street or supermarket a little. Say once or twice a week. The girl who thought she had seen me somewhere before, was it at a History lecture? The old lady who told me that my language was a disgrace, the man who thought I was a local newsreader, that kind of thing. Over the next few years as more television was done, Blackadders, Fry and Lauries and Jeeves and Woosters, the being-recognised-thing became something I had adjusted to. And over those same years it became more likely that they would know my name as well as my face. In other words I drip-fed into the public consciousness by a sort of osmotic absorption. My pheme was a slow attritional one. I was not like a soap star, teen idol or reality TV participant who, in the (famous) words of Lord Byron, wake up to find themselves famous. Their phemes rage and they are the people who usually find fame hardest to handle. They are typically very young and, by definition, they have not had four or five years to habituate themselves to the experience of being recognised. Rudeness, sulky gracelessness, drugs, drink, temper tantrums and so on are often the result. If they don’t have the imagination to know how much courage it takes for a member of the public to approach a famous person, then they let themselves down badly with their curt off-hand manner or their whining self-pity. Of course, it cuts both ways, plenty of members of the public don’t seem to have the imagination to understand what it’s like to be approached. As with all such social interactions therefore, a little from each is what’s required.

Small sidebar. I’m afraid there are plenty of words used by slebs to describe non-slebs. Here are some I’ve heard.

Mops/moppets – silly. It stands for Members Of the Public. Civilians – reasonable, but a bit John Goodman in The Big Lebowski. Ordinaries – ouch. Muggles – obvious and quite sweet I suppose. Punters – naff.

I’m sure there are many others. And now I’m sensing a certain amount of antagonism from some. How dare such valueless, vulgar, shallow little people with their adventitious so-called ‘celebrity’ develop a contemptuous slang for the decent, hard-working people who pay for these cheap weasels in the first place? Hm? Hm?????

Well yes, but we’re all human beings here. You would do the same. It’s not about being rude and one of the reasons you’d do the same is SCALE. Scale matters. If you’re accosted on average once a week, it’s charming. You can give a little time to the one who stopped you, be delighted by their knowing who you are and the whole thing can be a most pleasant and mutually satisfying interchange. If you are stopped every ten minutes then it’s a whole different deal. You keep your head down, pretend to be on the phone, wear dark glasses and generally hope to pass unnoticed. Or you get someone else to do your shopping, tube travelling and general street-using for you, sitting in the back of a Lexus most days and never interacting with the rest of the human race except when surrounded by burly security men who place their palms in the faces of anyone who dares to come near. Which is sad and can engender the reputation of being standoffish, grand and all the rest of it, but if the alternative is not being able to move around very easily, who can blame those afflicted with that level of fame? It’s the same with letters. Twenty to fifty a week you can just about keep on top of, reply to personally, strike up friendships, establish cordial relationships and so forth. Ten times that amount and rising and it’s all your secretary can do to filter the ones you might want to see from the ones that threaten to burn down your house and scratch your car. You’re the same person, no ruder, more off-hand or nonchalant than you were, but the scale alters how you can behave. The scale enforces a kind of distance that may be alien to your natural bonhomie.

The Tom Cruise Eye-Contact Canard Poor old Tom Cruise. If only I had a euro for everyone who has said to me in tones of wild, almost joyful disapproval, ‘apparently no one is allowed to look at him on the film set!’ (Actually the link I’ve embedded just there also shows how these ‘stories’ can be skewed for the purposes of some raving agenda, in this case a right-wing one). ‘Eye contact is banned!! I’m not making it up!! How mad is that?! Extras and crew are actually instructed not to stare at him!!’ In fact, a little imagination of the kind I asked you to summon up earlier and you might be able to picture this scenario: Tom Cruise (but you actually, because you’ve put yourself in his shoes) is about to do an important scene which involves hundreds of extras. He has to break down/shout/burst into tears/whatever. He comes on set to finish the camera line-up and get ready to shoot. Wherever he tries to rest his eyes there is someone staring at him. He is working, mind you, earning his fantastic salary (or if not earning it in your opinion, complying at least with its contractual imperatives), this is what he does, it takes concentration and skill, you may not value it, but take it from me, it isn’t easy. He has to prepare himself for whatever is required and then repeat the performance time after time for different camera angles. Put yourself in his position: you’re going to have to do something wild and daring in front of the camera and as you try to put yourself in the correct frame of mind there is nowhere to rest your eyes. Is it unreasonable to say to the Assistant Director, ‘would you mind asking all the background artists if they wouldn’t stare at me? Actually, knowing Asst. Directors, they would probably foresee the problem and make the announcement without consulting him even before Cruise ever arrived: ‘no one to stare at Mr Cruise when he’s on set.’ This gets repeated, comes to the ear of gossip columnists, mad republicans and others and it soon sounds like insane vain stardom all over again. When I was playing Wilde I had the same problem getting ready for the scene where Oscar comes out of the courtroom in handcuffs and is jeered and spat at. As the scene was being lit I couldn’t look in any direction without meeting the gaze of an extra, so I spent all the time staring at my boots or into a corner, like a naughty boy at kindergarten. I didn’t ask the AD if she’d put out a request for them not to look at me, but if I were in the same position again I might. Or I would spend the whole time in my trailer until the very, very last minute, which is bad for the director, the crew and the performance, not to mention the reputation of the actor who is forever set down in people’s minds as a Trailer Queen. But see how easily rumours of mad egoism get round? I’m not saying there aren’t wild egos amongst the famous, but sometimes it’s just a lack of imagination amongst the non-famous that sees insanity where all that lies behind it is professionalism and self-preservation. Many people of course have an ardent desire to want the famous to be deranged, spoiled, stupid and impossible to live with and perhaps some of you reading this will still choose not to believe me, preferring your image of star as pampered idiot child monster. It’s too much to bear that they have all the money, adulation and opportunity in the world, so let’s console ourselves with the thought that they’re deranged imbeciles so far up themselves it hurts. It is interesting isn’t it how very, very important money becomes (even to the most apparently spiritual) when criticising a famous person. ‘What are they complaining about? They’re paid enough aren’t they?’ as if money compensates for all things. Maybe it does in some people’s minds. ‘I’d put up with any amount of shit if I was paid that much.’ Would you indeed, how noble of you. I’ve seen enough of the very famous close up, film stars, sportsmen and musicians, to know it’s a pretty miserable fate. Happy superstars are a rare sight. Not many seem to want to believe that, but it’s true.

Be yourself Plenty of people have said to me in supermarkets in slightly affronted tones ‘what are you doing here?’ as if I had no business being in such a place. I long ago gave up answering with a silly sarcastic ‘playing badminton, taking a shower, duh, shopping!’ kind of answer. The way to respond is with a ‘gosh, I know! Isn’t life silly! Aren’t I daft!’ sort of grin. ‘Tch, I don’t know! Aren’t we barmy just for being!’ For everyone who looks down on a famous person for not shopping in the supermarket or using the bus, there are those outraged to see them doing just that. Some want our famous people to shop only in a fantasy Famous People Village, to zoom about in limos and use special extra private double-secret VIP lounges – others hate them for doing just that.

The lesson for the sleb is be who you are, not what you think others want you to be. Otherwise you’ll get yourself in a pickle by putting on a mockney accent believing that ‘the people’ will be impressed by how ‘real’ you are, whereas we all know nothing grates more. Conversely you might give off a false air of dining every night at the Ritz when in fact you’re happier in the local chippy. No need. Be yourself.

Negatives There are drawbacks to fame, of course there are. The scaling up and the misinterpretation are two that I’ve mentioned. By the way, just as one can have bad hair days, so one can have bad fame days. There are days when try as I might I cannot go unnoticed. It’s as if I’m walking around with a neon sign over my head. Every cab driver, everyone I pass in the street, every shop assistant stops me and asks for an autograph or photo (of which more later). I can lower my head, concentrate on looking anonymous, but it’s no good. On other days I could lope about in fluorescent clothing meeting everyone’s gaze and nobody would take any notice. Seems to defy logic but anyone in the public eye will tell you the same. ‘Weird, I’m really famous today,’ is how one might put it. Back to drawbacks …

Mood Famous people are not allowed to be in a bad mood in the way that everyone else is. ‘We made you, we paid you, you will therefore look cheerful and contented (but not smug) at all times.’ This is difficult to live up to. The day comes to all of us when we’re not in the best of moods. It comes to me big time on occasions. I have made this public by talking about my mood issues, my bipolar disorder, but even if I weren’t so especially afflicted, I would, like any human, have cheerful days and less cheerful days. But woe betide the famous person who wanders about with a scowl on his face. Passers-by will read all kinds of things into a sour expression: ‘what a misery!’ ‘I suppose he thinks he should be served first because he’s famous!’ ‘Does he expect us all to bow down and worship him?’ etc etc. All of it incredibly unfair and not something we would presume to read into the facial expressions of a non-famous person, but we can’t help it. They are famous and therefore we can impute all kinds of motives and attitudes. A daffy smile is therefore at all times de rigueur. A sort of ‘tsk, don’t mind me, I don’t know, golly isn’t life potty, still mustn’t grumble, ho, goodness, I say, don’t you think, hm?” sort of expression that covers all eventualities in an English self-effacing, I’m-embarrassed-by-my-own-existence sort of way.

Who are you? A fair chunk of the population does not care to be reminded that they themselves are not well-known and their default position when it comes to the famous is one of scepticism, contempt, out-of-my-way-I-really-have-no-idea-who-you-are resentment; expect from them narrow frowning as they stare at you in a way that they really want you to notice: it says, ‘I think I may have seen you somewhere before, but my life is too busy and my standards too high to know exactly who you might be. If you care to approach me and tell me who you are I might pay you some attention, but otherwise I find you faintly annoying.’

“You must get really fed up…” A very, very, very popular strategy used by the approacher is to cast themselves in the role of the non-typical fan. This of course is the most popular method and casts them therefore as utterly typical. They will say something like ‘I expect you get really annoyed by people coming up to you…’ as if they are not doing exactly that. A very, very well known friend of mine once actually called the bluff of this social pretence, which was excessively naughty of him. It went like this.

Fan: You must get really annoyed by people coming up to you all the time. Fameboy: Not at all. The only thing that really annoys me is people coming up to me and telling me that they expect I get really annoyed… Fan: Well, fuck you then! (exit huffily)

Fan became ex-fan and my friend spent the rest of the decade kicking himself, for he is not usually rude or mean.

It is obvious and wholly understandable that when people approach you they want to present themselves as separate from the herd: they are not aware that the more they attempt to be different the more they are in fact identical. When I had a crush on Donny Osmond I was convinced that if he could only get to know me he would discover that I was so different from everyone else around him that he would understand how we were meant for each other. This is Stance A, the Standard Defining Fan Feeling, and covers the beliefs of all fans from obsessive to faint admirer.

Unique Opening Line As far as I’m concerned, I really don’t expect people to be original, and if they were all to say ‘I expect you get really annoyed…’ (which they just about do) I honestly wouldn’t mind. Better that than cudgel their brains for some unique opening line. It’s common for the Unique Opening Line to be something surreal about biscuits if it’s a teenage boy or a comment about the shoes/tie one’s wearing if it’s a girl. I don’t know why, but there we are. I report as I find. What I dread most, however, is the Arcane Factoid.

The Arcane Factoid Now that does happen from time to time. Because of QI I’m very often asked a trivia question along the lines of ‘what’s the name of the plastic thingy at the end of a shoe-lace?’ in fact I must have been asked that particular question at least 20 times. I’m not exaggerating. It’s one of the class of facts that people believe they are the only people in possession of. Aglet, by the way, is the answer, though as we geeks know, aglet has another meaning too. As if you didn’t know. Naturally there are plenty of questions that I don’t know the answer to, and this allows people to go off happy in the knowledge they have bested me and that I am not the font of all wisdom that I never said I was. ‘I bumped into that Stephen Fry in Waitrose and he never even knew the name of the dog who found the stolen World Cup’ or whatever… If not a factoid a muddle-headed origin. ‘Did you know that the V-sign comes from the archers at Agincourt?’ I have given up replying, ‘no I didn’t know that, and the reason I didn’t know it is because it isn’t true.’ People like to believe their derivations and origins, no matter how wrong they are.

Sample dialogue Now this is all beginning to sound as if I’m contemptuous of the people who come up to me in the street. I’m not. I’m genuinely not. The huge, vast, enormous, colossal, gigantic majority are kind, sweet-natured, friendly, unobtrusive, understanding and delightful. I’m merely sharing the experience with you as best I can. The fact that people say the same kinds of thing does not make them predictable, dull, foolish or uninteresting. Those who try and come up with something completely original or who fish for some connection (‘my father knew your doctor’s accountant’s sister-in-law’) are more tiring and more of an intrusion into one’s day, certainly. It would be dishonest of me to deny that and you wouldn’t trust me if I pretended that I thought all people were equally good company. You’d think I was a dick. Charm should be rewarded. In the end I it works best when both sides recognise that it’s a social dance and want to get it over with as quickly as possible.

You: Hello there. Nice to see you round these parts. Me: How very kind of you. Thanks very much. You: What brings you to Doncaster? Me: Oh you know, where else would I want to be on a Wednesday? You: (chuckling) The countryside around is attractive though. Me: Yes, lovely. Hope to see more of it. You: Right, well. Keep up the good work. Me: Thanks. (exit)

End of story. Compare this to.

You: I know you probably get really annoyed by people coming up to you. Me: No, no. Not at all. You: No, it must be really irritating. Me: Oh, well. Goes with the job … You: You probably just want to be left alone. Me: Well, you know … You: What makes people bother you all the time? Don’t they know you’ve got the right to a private life? Me: Mm. You: Makes you sick. Love your work, by the way. Me: Thank you. You: I’m not like some mad fan, you know, but I used to watch that a Bit of Hugh and Laurie… and that IQ thing you do. Me: … QI … You: Right. That Alan Davies, what’s he like? No, really. What’s he like? Me: He’s very nice. You: Yeah, but is he that stupid? Me: He’s not stupid at all. You: No but he is, isn’t he? Me: No, no, not at all. Quite the reverse. You: Right, thought so. Do you remember your parents used to shop at a delicatessen in Norwich called Lambert’s? Me: Er … yes, that rings a bell. You: My girlfriend’s mum had a friend who worked there. Me: Gosh, really? You: Amazing, isn’t it? Me: Astounding. Look, I really must … You: Do you know what C. S. Lewis’s middle name was? Me: Er, Staples I think. You: Oh. Someone must have told you that. Me: Well, yes, a biography of C. S. Lewis. You: Most people don’t know that. Me: Don’t they? Well, well. Gosh, I must be … You: Must be very annoying having people just come up to you. Don’t know how you put up with it … have you got a pen? Me: Excuse me? You: Or a piece of paper? Tell you what, can you sign this pack of biscuits. Oi, darling, lend us a pen, see who I’m talking to? … Etc.

Compliments The entire interaction works better if there’s a little understanding on each side. You might be the fortieth person that day to approach your sleb. They might have just heard that their favourite aunt has been diagnosed with cancer. On the other hand, the famous person should remember that it takes courage to approach a stranger, especially one you’ve only seen on TV or at the movies. They could so easily squash you. Many newly made slebs fall down especially in the area of compliments. It’s perhaps a very English thing to find it hard to accept kind words about oneself. If anyone praised me in my early days as a comedy performer I would say, “Oh, nonsense. Shut up. No really, I was dreadful.” I remember going through this red-faced shuffle in the presence of the mighty John Cleese who upbraided me the moment we were alone. ‘You genuinely think you’re being polite and modest, don’t you?’ ‘Well, you know …’ ‘Don’t you see that when someone hears their compliments contradicted they naturally assume that you must think them a fool? Suppose you went up to a pianist after a recital and told him how much you had enjoyed his performance and he replied, “rubbish, I was awful!” You would go away thinking you were a poor judge of musicianship and that he thought you an idiot.’ ‘Yes, but I can’t agree with someone if they praise me, that would sound so cocky. And anyway, suppose I do think I was awful?’ (which most of the time performers do think of themselves, of course.) ‘It’s so simple. You just say thank you. You just thank them. How hard is that?’ You must think me the completest kind of arse to have needed to be told how to take a compliment, but it was an important lesson that I (clearly) never forgot. So bound up with not wanting to look smug and pleased with ourselves are we that we forget how mortifying it is to have compliments thrown back in one’s face.

Cameras!! When I wrote my first couple of books back in the late eighties, I found one of the most enjoyable aspects of being an author was the Event. This is publisher-speak for appearances in bookshops, talks, readings, lectures, literary festival on-stage interviews, plenary sessions, symposia and other such author-related public appearances. Each event would end with a signing. The queue would shuffle along, each customer would plonk a book down in front of me, we’d shoot the breeze for a while, author and reader in merry harmony, then they’d biff off to be replaced by the next in line. All very pleasant and genial. Occasionally, just every now and then, someone in the queue would have a camera and there would follow a rather complicated and painful procedure: the one with the camera, A, would have to find someone, B, willing to take a picture. Sometimes B would be the next person in the queue, often a member of the bookshop’s staff. B would be given the camera, while A would go behind the signing table to put an arm round me or a hand on my shoulder as I signed the book with a flourish while looking up into the lens with grinning soupily. Of course B wouldn’t be acquainted with A’s particular make of camera. In fact B would give the impression of never having taken a picture before in his or her life. Wrong buttons would be pressed, extra shots would be taken ‘just to be sure’. The flash would fail to go off. A would have to go round the table again to twiddle with knobs and eventually, after much delay the business would be done. It wasn’t too disastrous, at most one or two people in the whole signing queue would be armed a camera. It wasn’t too awful an imposition.

But today …

Today everyone has a camera. They have a dedicated digital machine or something built into their mobile phone. As a result of this ubiquity the signing queue has become such a living hell that I don’t do them any more. All the pleasure has been sucked out. No agreeable exchanges and chats with the readers, nothing but the unspeakable horror of having to put up with 200 hundred versions of the awkward and excruciating performance described above. The agony is especially exquisite given that the type of people who attend literary events and are interested in my books are precisely the type least competent at operating other people’s cameras. They may be able to use their own, but that’s of no importance because the crucial prize (which has all the point, purpose and value of twitching or train-spotting) is for the camera owner to be in the picture with the poor sap of an author. Given that the one thing that actors, writers and performers most hate (and I’m an extreme example) is having their photograph taken, life has now become a kind of living hell. It’s bad enough with professional photographers in studios (and believe me, it really is bad enough, I loathe the experience), but to have to freeze the face into something akin to a smile time after time after time while the bewildered operator footles uselessly about with the tiny little tits hat pass for buttons and switches. The photo software is so diabolically crap on most phones anyway (I have to say the Apple iPhone is astoundingly good in this respect, even a literary woman could operate it, and it is better quality than cameras with twice the pixel count) that you can hardly blame people for not being able to use it. It’s hardly surprising they switch it off every time they mean to shoot, or that the screen goes black or it’s in video mode or some other problem. It’s hardly surprising because as a piece of kit it’s bollocks. In the meantime the frozen smile fades, the queue behind gets restive and all the good vibes turn to bad.

But it doesn’t end there …

The camera and all its horrors are by no means confined to the literary events which one can (as I now do) decide to leave well alone. The fact is everybody has a camera whatever the time of day or night.

So you can almost forget everything I wrote above about people’s conversational gambits, because a conversation is a rarity these days. Today it’s the crushing embarrassment of standing in the street like a gibbon while a total stranger accosts other total strangers and asks them to take a photograph. Crowds gather, what could have been a quick anonymous chat has become a full-on photo-op. ‘Me too!’ ‘Hold still!’ ‘Oh, and can you do a General Melchett “Baaah!” so I can use it as a ring tone? Hang on, where’s the recording app?’ ‘Say hello to my girlfriend, she doesn’t believe I’m talking to you.’ ‘Could you say in a Jeeves voice, “this is Kevin’s phone, the master is out so would you please be kind enough to leave a message?” Blinder!’ etc.

Oh, bring back the days of the simple autograph.

Your Friends If I were to ask one thing of people in their interaction with the famous it is this: consider the companions. Imagine what it is like to be in the company of a well-known person, a person who could be your brother, sister, mother, life-partner, school-friend, client, patient. You’re chatting away and someone barges in on your conversation. They completely ignore you, indeed often literally elbow you out of the way, planting their back in your face. You patiently stare into your soup and watch as your famous friend/lover deals with them charmingly and eventually manages to end the exchange. Who has suffered most? The famous person? No, he or she knows perfectly well how to deal with this, has accustomed themselves to these encounters and is, after all, usually the beneficiary, is made to feel important. But the companion! They are made to feel the opposite of important. They are at best ignored and at worst resented for taking up the time and conversation of the famous person in the first place. “Who do you think you are, dining with them as if you owned them?” It is awful, awful, awful having to accompany a well-known person in public. On the first few occasions it might be instructive and interesting to a student of social anthropology, but in the end it’s a pain, a real pain. So if you ever do go up to someone well known, consider that point.

Watching fame happen I have grown well-known in my own land, and slightly known in other lands, and I have watched others grow very well known indeed. When I made Wilde in 1996 I was much better known that my co-star Jude Law who is now internationally famous as a film star in a way I will never be. When I directed James Mcavoy and David Tennant in Bright Young Things they were complete newcomers. I am proud, if that doesn’t sound possessive, of the splendid way they have dealt with their very fast leap up the ladder of fame. They have the advantage of very considerable talent, of course. To be famous and talentless, that is the curse. If you are rich and feel uncomfortable with the money, you can give it away in one stroke. To lose your fame takes time.

The plus side How graceless I sound, listing all these negatives. Do forgive me. I completely understand that to be well-known is to be blessed with all kinds of advantages. I completely understand that fame is something that many, if not all, hunt after in their lives. I know that fame usually suggests the accompaniment of money, admiration, opportunity, an easy acquaintanceship with interesting and extraordinary people, tickets to hot events, freebies and all the rest of it. I know that some people value all these things above rubies and that they yearn for fame and its accoutrements more than they yearn for the talent or achievement that might bring them in the first place. Nothing I can say about fame’s drawbacks (and we haven’t even started on what harm fame may or may not do to one’s soul) will sound anything other than curmudgeonly and ungrateful to many people reading this. Which is why no one usually talks about the experience of fame at all. It’s best to shut up about it. Plenty of people talk about “the celebrity culture” but very few discuss fame itself as an experience. If there are a few wasps at the fame picnic – paparazzi, mean people, those determined to misunderstand you, those who embarrass you, stalk you, plague you – it is still a picnic and it doesn’t do to moan. I hope you’ll understand that nothing I’ve written so far is a moan: just a few observations I thought it worth sharing. I’ll be misunderstood, misinterpreted, of course I will. That’s another of the wasps. But the pork pies, chicken leg and white wine still make the whole fete champetre entirely worth while.

© Stephen Fry 2007

Note: Yes we do hold comments to be moderated, Producers.