Column “Dork Talk” published on Saturday January 12th 2008 in The Guardian

“Social networking through the ages” – The Guardian headline

There is some deep human instinct that compels us to take a wild and open territory and divide it into citadels, independent city states, MySpaces and Facebooks

Much ink, electronic and atomic, has been expended on the subject of social networking and web 2.0. First, let’s decide on how this last is pronounced. “Web two” won’t do. “Web two point oh” is common, but I heard it as “web two dot oh” from the lips of Sir Tim Berners-Lee OM himself and since he is the only begetter of the web, I shall take my lead from him, the most influential Briton since… well, he has no rivals. Brian Blessed, perhaps.

Web 2.0 was christened, so far as I am aware, by Tim O’Reilly. Oh really? No, sir, O’Reilly. He was one of the early advocates of open source programming, and greatly championed Perl, the language my father speaks fluently but which involves too much brain power and concentration for the likes of me.

These days web 2.0 refers both to user-generated content and to social networking sites. Rather than passively searching, browsing and eyeballing the billions of pages of the web, millions now contribute their videos, their journals, their music, their photos, their lives.

The Big New Thing

Social networking (Facebook, MySpace, Bebo, etc) has been identified as the Big New Thing. In other words, people who watch My Family have now heard of it and are at last aware of the difference between downloading and uploading. A sure sign, perhaps, that the phenomenon is on the way out. MySpace is already as seriously uncool (and as hideously girlie, pink and spangly) as My Little Pony; Facebook is taking its advantage (openness to having applications written for it) to such extremes that it’s in danger of losing the original virtues of elegance, intelligence and simplicity that established it as a classy, upmarket place in which to live a digital life in the first place.

I am old enough to remember Prestel and the original bulletin boards and “commercial online services” Prodigy, CompuServe and America Online. These were closed communities. You paid a subscription, dialled in and connected. You made new friends and you chatted in “rooms” designated for the purpose according to special interests, hobbies and propensities. CompuServe and AOL were shockingly late to add what was called an “internet ramp” in the 90s. This allowed those who dialled up to go beyond the confines of the provider’s area and explore the strange new world of the internet unsupervised. AOL offered its members a hopeless browser and various front ends that it hoped would keep people loyal to its squeaky-clean, closed world. This lasted through the 90s as it covered the planet in CDs in an attempt to recruit subscribers. A lost cause, naturally, and the company ended up as little more than an ordinary ISP. Made millions for Steve Case on the way as AOL merged with Time Warner, but that’s another story.

Opening and closing like a flower

My point is this: what an irony! For what is this much-trumpeted social networking but an escape back into that world of the closed online service of 15 or 20 years ago? Is it part of some deep human instinct that we take an organism as open and wild and free as the internet, and wish then to divide it into citadels, into closed-border republics and independent city states? The systole and diastole of history has us opening and closing like a flower: escaping our fortresses and enclosures into the open fields, and then building hedges, villages and cities in which to imprison ourselves again before repeating the process once more. The internet seems to be following this pattern.

How does this help us predict the Next Big Thing? That’s what everyone wants to know, if only because they want to make heaps of money from it. In 1999 Douglas Adams said: “Computer people are the last to guess what’s coming next. I mean, come on, they’re so astonished by the fact that the year 1999 is going to be followed by the year 2000 that it’s costing us billions to prepare for it.”

But let the rise of social networking alert you to the possibility that, even in the futuristic world of the net, the next big thing might just be a return to a made-over old thing.

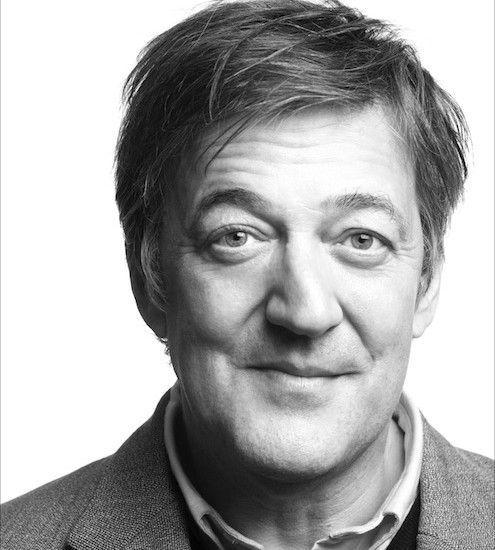

© Stephen Fry 2008