A deadline met: such relief. You would think that after so many years I might have mastered the art – not of writing – but of putting myself in a position to write. Many writers are, like me, fascinated by process. From an early age I wanted to know whether authors worked by morning or night, whether they typed or wrote by hand and if so on what kind of paper, whether they had their backs to the window, drank wine, sat, stood or lay on their backs with their legs in the air.

I don’t profess to understand the reasons, but I work best in the mornings. And by mornings I mean mornings. When I have any serious piece of writing to complete I start by getting up early, about 6 say, and I sit in front of my computer screen till mid-afternoon. As the days pass the hour of rising becomes earlier and earlier until I’m going to bed at 7 or 8 at night and flinging back the duvet ready to write at 4 or even 3 in the morning.

In the old days I used a manual typewriter until I graduated to a golfball and finally one of those Brother machines that could keep a whole line in RAM before printing it out. I usually scribbled in longhand first, something I still often do. In 1982 I bought a BBC Acorn for £399. It came complete with a firmware programme called Wordwise which I adored and which, in my fond memory, was the best word processor ever. I used it to write the book (ie story and dialogue) of a stage musical, saving on cassette tape as I went along and finally outputting to a daisywheel printer. The show was enough of a hit to allow me to indulge my passion for computer gadgetry for the rest of my life. I still tremble at the insanity which propelled me to outlay £7,000 on an Apple Laserwriter in the autumn of 1984. But the gear, gadgets and gismos were ultimately irrelevant of course. It was all about coffee and cigarettes. Sitting in a study in Norfolk, curtains drawn (I cannot bear natural light when I’m writing), staring at that flashing I-beam on the screen. Cursing at the cursor.

Other writers may have written in the afternoons, used school exercise books and coloured pencils, sipped water and gazed out of the window but my way was my way and by the time I had written my first novel a kind of superstition told me that it would be tempting providence to change. I might frighten off those shy Muses. So, aside from the miracle of managing to give up cigarettes two and half years ago, I have kept to the same system. Well, system is hardly the word. But … it’s still so bloody difficult. I may always have been weirdly fascinated by the processes and outward routines of other writers, but deeper than that I really needed to know how much they too grunted, swore and howled at the sheer horror of having to write. “I sit at the typewriter and curse a bit,” said one of my earliest literary heroes, P. G. Wodehouse. Was he a special case?

I began writing seriously when I was about thirteen. Out streamed poetry, stories and novels, the latter of which were always aborted early, usually half way through the second chapter. It took my friend Douglas Adams to encourage me to go further and he did this by pointing out that the reason I had never managed to finish a novel was that I had never properly understood how difficult, how ragingly and absurdly difficult, it is to do. “It is almost impossibly hard,” he told me. It is supposed to be. But once you truly understand how difficult it is,” he added, with signature paradoxicality, “it all becomes a lot easier.” It was many years later that Clive James quoted to me Thomas Mann’s superb crystallisation of this “A writer,” said Mann, “is a person for whom writing is more difficult than for other people.” How liberating that definition is. If any of you out there have ever been put off writing it might well be because you found it so insanely hard and therefore, like me, gave up and abandoned your masterworks early, regretfully assuming that you weren’t cut from the right cloth, that it must come more easily to true, natural-born writers. Perhaps you can start again now, in the knowledge that since the whole experience was so grindingly horrible you might be the real thing after all. Of course finding it difficult and managing to complete are just the first stages. They are what earn you the uniform and the brass buttons, as it were. They don’t guarantee that what you complete is any good, or even readable. That is quite a different kettle of wax, a whole other ball of fish.

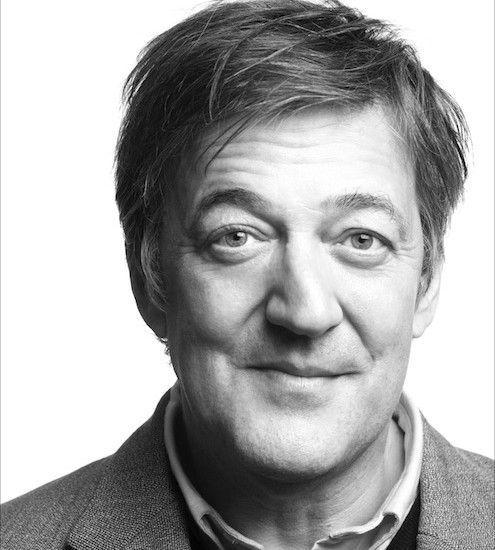

You might notice below that another of my peculiar writing habits is to leave off shaving while the authorial fever is upon me. I believe Tolstoy and Gertrude Stein were the same. Pip pip.