100 Greatest Gadgets

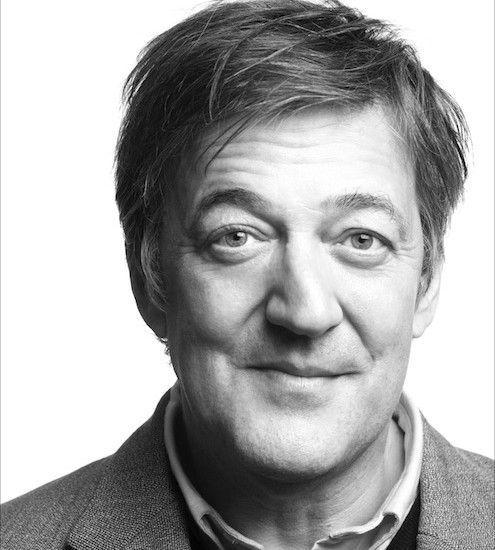

On Bank Holiday Monday Channel 4 are screening one of those “100 top” programmes they like to make and this year I had the pleasure of being allowed to choose my 100 favourite gadgets. I don’t think you’ll guess which comes first. Besides, I didn’t really approach it as a beauty pageant. The winner might as easily be a kitchen essential as a digital doodad. The fact is I have always had a quite inexplicable love of gadgets and feel myself blessed to have been born into an age in which they seem to have come thicker, faster, newer, sleeker and more miraculous than ever before. In the programme we didn’t want to get all ontological on your arse and never made an attempt to define or limit the meaning of the word. A gadget, for our purposes, was more or less what I decided it was, and in the end it doesn’t really matter who wins the Palm D’Or. Though naturally your burning curiosity will keep you watching all the way to the finish because …. well, you’ll never guess. You’ll just never guess…

But it’s talk of palms, d’or or otherwise, which brings me to the sad story of the week. Of the year. Of the decade.

The early days…

I’ve always been a lucky sod when it comes to my love affair with all things tech. It is a passion that coincided with my having a career that allowed me to be able to indulge in the kinds of insane spending spree that the speedy inbuilt obsolescence of gadgetry has always necessitated. At some time in 1985 I astonished my friends by brandishing before them professionally printed material. I remember the late and blessed Ned Sherrin goggling in disbelief when I came into a radio studio with a piece of A4 on which my script had been perfectly printed.

“You send your scripts to a printer?” he shrieked.

I nodded gravely. “These are fine scripts,” I said. “They deserve memorialisation.”

It was only after being harangued for insanity, hubris and dementia that I finally confessed that I had invested in a new kind of printer. You must remember (or be told because you are far too young to remember) that in 1984 printers were dot matrix machines that produced only a faint simulacrum of what a printing press could manage. In 1985 Apple brought out the LaserPrinter, Aldus produced a programme called PageMaker and I had splashed out £7,000 for one and about £40 for the other. A ridiculous sum, but I was now a Desk Top Publisher. The PostScript language, kerning, leading and justification were all I could think about.

Less than ten years later I ambled into a film studio and started taking photographs of the set with a QuickTake camera, much to the astonishment of the cinematographer and his crew.

“What’s more,” I said, “I could upload the photographs to my computer and email them to a friend.”

“What’s email?” they all wanted to know.

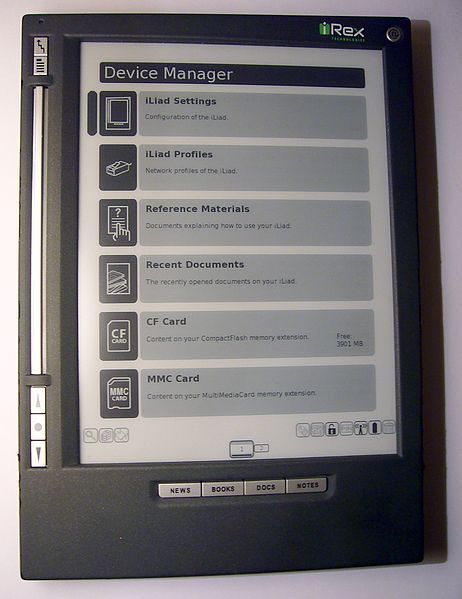

That digital cameras, perfectly printed pages and email are now all as platitudinous, quotidian and meretricious as takeaway coffee is easy to take for granted and I certainly don’t expect credit for being an early adopter or some kind of wise prophet. I was also an early adopter of many disastrous failures. The Newton, the Microwriter AgendA, early, bulky and dreadful Sony electronic books, iRex iLiads weird tone-dialling devices – any number of freakish gadgets that were either before their time and technology or simply deluded and hopelessly hopeful were all grist to my crazy mill.

The Mac, the LaserWriter and QuickTake camera were (niche and generally unprofitable) Apple products and it’s hard now to believe that there was so long a period when friends and the entire tech press gleefully crowed that my aging Mac peripherals and spare parts would in future have be bought at specialist hobbyist shops because Apple as a company was doomed. Well in 1997 Steve Jobs returned to the company he co-founded and that had fired him 12 years earlier and everything changed, but enough of that.

A tiny sector of the gadget market…

My real passion in those days was not for things Apple but for a small and for a long time unnoticed sector of the market – one that Apple did have an early brave stab at, as had many others with equally doomed results, but which was truly ruled for what seemed an age by Psion and then Palm and Nokia. I am talking about those little objects that started out as PDAs and morphed, almost without anyone noticing, into smartphones.

If you (are masochistic enough to) go back five years or so and consult the earlier tech blogs section of this site you can find examples of me banging on about my love of those early devices. The world has moved on hugely since then, but this week has laid a final wreath on the grave of a much loved (by me) innovator.

British to the core…

It is not meant as a patriotic boast, but it is certainly remarkable that the ARM processors behind almost all modern mobile phones, the Symbian OS that reigned supreme for so long, the design of iMacs, iPods, iBooks, iPhones and iPads and indeed the world wide web itself have all been largely the work of Britons. Of course, good science and technology depends upon shared resources and Berkeley’s RISC was the foundation of ARM; Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the father of WWW, always maintains that his work was part of an ongoing process, Jony Ive never fails to mention his fellow designers at Apple while Symbian … well, poor old Symbian is all but forgotten these days, indeed Nokia’s stubborn clinging to it is regarded as one reason for the Finnish giant’s less than impressive performance of late – despite the billions of Nokia badged phones that are still used around the world.

Symbian began life in Britain as EPOC, an operating system created for Psion handheld devices. The Psion Organiser 2 was the first really impressive, in my opinion, Personal Digital Assistant. I was a loyal user, indeed had the honour to help with the launch of the Revo in 1999. EPOC’s transformation into Symbian was taken up and run by Nokia, Ericsson and Motorola in an attempt to create some sort of standard Operating System for reasonably low-powered, ARM processor toting mobile phones. It was never entirely standard of course, nothing ever is, all kinds of flavours soon developed, UIQ, S60, Anna and the lord knows what else, but with the Nokia Communicator in 1996 Symbian really managed to strut its stuff as a proto-smartphone OS. You could send emails, browse the web, store contact numbers and calendar entries and even add what we would now call apps – all in monochrome with navigation and control achieved by cursor buttons rather than touchscreen, but for those of us lucky enough to own one it was about as exciting as could be. Val Kilmer used one as Simon Templar in The Saint, I recall, that’s how cool it was.

Shirt pockets…

Across the Atlantic things were moving in a different direction. I became fascinated by the US challenge to the Psion and Communicator, the Palm Pilot, a device which answered a peculiar American imperative in that in could fit into an office worker’s shirt pocket. Corporate Americans wear (usually white) shirts which always have a pocket round about where the left nipple might be on a human being and woe betide any hardware manufacturer who even thinks about producing an object that exceeds this unalterably insistent form factor. The size limitations required Palm to think hard and, like a poet forced into the sonnet form, they came up with marvellous solutions.

The Palm Pilot had a touch sensitive screen, not the capacitative type we now all know and love in the modern smartphone or pad, but the resistive kind which required the use of a stylus, or when lost (as it inevitably was) a finger nail, empty biro or the tip of the arm of a pair of spectacles. Handwriting of a kind could be achieved by forming characters from a cut down, shorthand version of the alphabet known as Graffiti (sideways on but a nostalgic reminder). Graffiti could very easily be mastered and allowed immensely speedy input. I adored it and used it when it reappeared for a while on the Newton, on Sony P900s and even, bless them, early WinMob devices where they called it “block” or something similar. Now it’s available (of course) as a retro app for Android and iOS.

Handpsring…

Palm was acquired by the 3M company and its original creators and founding geniuses moved away to found Handspring which came up with first the Visor and then, joy of joys, the Treo. The Treo 180 (or 180 g for Graffiti lovers ) was a Palm Pilot into which you could slip a GSM SIM. It had a stubby little aerial, a beautiful flip screen, guess-ahead contact dialling and many of the features we now regard as standard but which were then little short of revolutionary. It could be synced with one’s computer, and (as it iterated all the way into the Treo 600) it allowed full colour web browsing. It was a real smartphone, its battery lasted all day, you could swap SIM cards at will, Matt Damon used one in the first of the Jason Bourne movies, for heaven’s sake. Matt Damon. That’s how recent and yet how far distant the PalmOne (as Handspring became) and its PalmOS were and are.

Throughout the greater part of the first decade of the twenty-first century nothing came close. Microsoft produced the hideous, cumbersome ugly and all but unusable WinMob OS in various numbers. Nokia continued with Communicators before, sadly (for me anyway) abandoning them. Sony never quite got the P900 series right. So perfect but so flawed and so-o-o liable to crash.

But…

Palm was IT. They made arses of themselves by producing a Treo that ran Windows. This alienated everyone who liked the simplicity and ease of the Palm OS and was the first indication that they might be losing the plot.

Then in 2007 two things happened that changed the landscape for ever. Palm produced the Foleo , a dumb terminal netbook and a month later Apple produced the iPhone. The Foleo lasted little more than three months. Apple had changed everything.

How to respond…

Palm scratched their heads and saw that multi-touch, app-rich full laden smartphones were now here to stay. They realised that WinMob was no way forward and that Apple was not about to licence anyone else to use its iPhone OS. Rumours abounded of an Open Handset Alliance, led by Google who would come up with something to answer Apple’s transformation of the market. Palm decided to devise their own challenge and it was to be in the form of devices powered by a Web based OS, in other words an operating system for smartphones whose apps were written in the same language/s that runs the world wide web. Many Google services default to web app version when you browse to them on a mobile. Amazon have just produced a web app version of their Kindle reader to get round Apple’s prohibitive policy of denying the iOS version direct click access to the Amazon store. Web apps, in other words, are far from a dead duck and an WebOS struck most commentators at the time of Palm’s announcement as an excellent and exciting idea. I certainly salivated at the thought.

The rest is history…

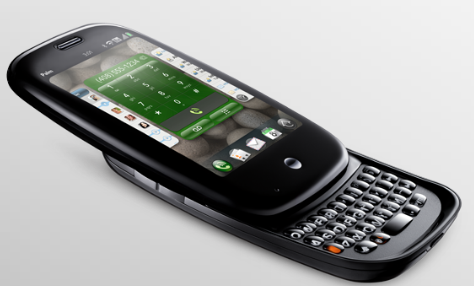

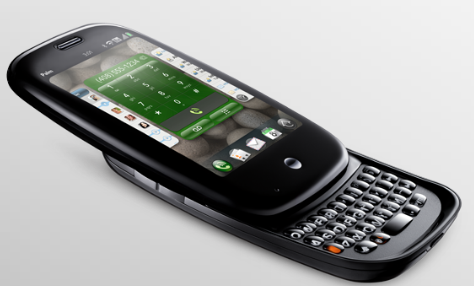

The Palm Pre arrived. Too late. Too small. Underpowered. You could fit two into an American office worker’s shirt pocket, for heaven’s sake. I owned a couple of Pre devices, an American CDMA and a European GSM version. I so wanted them to work. I liked a lot of what they did and how they did it. Blackberry has incorporated some of the original WebOS gestures into its Playbook, a frustrating but in some ways (to a contrarian like me) rather appealing tablet about which I might write another time.

In short, the Pre failed to catch on. It was a disaster for Palm. Their owndership of the American businessman’s shirt-pocket, which once seemed so assured, was over. More than that, the company itself was done for. Hewlett Packard bought them for $1.2 billion last year. HP announced they would integrate Palm’s WebOS into a series of hand held and tablet style devices and go at this huge and growing market with all guns blazing. They introduced the WebOS powered TouchPad less than three months ago.

HP Sauce…

Then, last week, HP announced it was withdrawing completely from the hardware business, whether in terms of laptops, desktops, smartphones or tablets.

So now only Windows Phone 7, Microsoft’s vastly improved mobile OS, Android and Apple’s iOS remain to fight over the world’s smartphone customer base. Nokia has more or less given up on Symbian and will concentrate on producing Windows 7 devices as a hardware manufacturer. HTC will carry on producing cute and serviceable candy-bars for both Android and Windows 7 while Apple will continue to do, presumably, what Apple does. RIM meanwhile have a foot in each corner. They have retreated to their proven customer base with the introduction of a restyle up-to-date version their best BlackBerry, the Bold, while refusing quite to let go of the Playbook or the hybrid Torch, a BlackBerry that thinks it’s a multitouch but isn’t too sure.

I have that new Blackberry Bold 9900, a Playbook, an HTC HD7 Windows phone running “Mango” and an Android HTC Sensation as well as an iPad 2 and an iPhone 4 (both running iOS 5 and the iCloud with Lion OS X 7.2 beta because I’m a sad nerd who forks out for a developer’s account) – I have run, and always, will I suspect, run as many devices alongside each other as I can for the foreseeable future.

But then, as AOL and Psion and Nokia and Palm will tell you, the future is not very foreseeable at all. And I can see that it never will be. Er … I think.

I do shed a tear however for the demise of Palm and their WebOS. Any turn of events that reduces biodiversity in the smartphone sector saddens me, and I mourn and memorialise the ingenuity, imagination and innovative genius of Palm and its original founders.

x Stephen