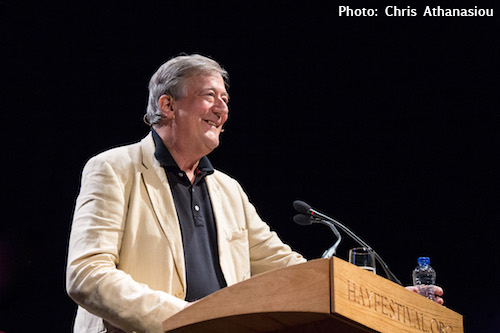

Transcript of lecture delivered on the 28th May 2017 • Hay Festival, Hay-on-Wye

Peter Florence, the supremo of this great literary festival, asked me some months ago if I might, as part of Hay’s celebration of the five hundredth anniversary of Martin Luther’s kickstarting of the reformation, suggest a reform of the internet. Firstly let me say that, despite a lifetime immersing myself in what I consider the provoking, beguiling, bewitching and often befuddling joy of technological development, especially in the realm of information technology, networking and shiny digital devices, I am no computer scientist, coder or programmer. Many people, some of them no doubt here in this tent now, will know much more about the subject I’m going to discourse upon. Take this, if you take it all, as the offering of a curious mind, curious in both sense, avid for information and just plain odd.

You will be relieved to know, that unlike Martin Luther, I do not have a full 95 theses to nail to the door, or in Hay’s case, to the tent flap. It might be worth reminding ourselves perhaps, however, of the great excitements of the early 16th century. I do not think it is a coincidence that Luther grew up as one of the very first generation to have access to printed books, much as some of you may have children who were the first to grow up with access to e-books, to iPads and to the internet.

Johannes Gutenberg’s great project, his Bible, bore fruit in 1455 – perhaps 120 or so copies on paper and 60 on vellum, calfskin – but Gutenberg had in fact already given this new art of moveable metal type printing a trial run, a proof of concept, in the production of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Papal indulgences. An indulgence was a piece of paper, signed and sealed by the Vatican. Whoever could afford such a holy ticket could buy it and be … well, indulged. They could, in effect, sin – up to and including the face value of the indulgence they bore, which held good, officially for no more than 40 years, but indulgences were soon produced with expiry dates of 20,000 and in a few recorded cases 45,000 years, allowing the lucky purchaser to go straight to paradise without passing purgatory. Just as you can buy carbon credit now, so you could buy this Vatican vice voucher, a sin offset document. The Church originally had their monks and clerks write these by hand, but then, thanks to Gutenberg, they had thousands of them printed at a fraction of the cost, to raise money for, amongst other things the completion of St Peter’s in Rome but also – as Luther noted – for the lining of individual pockets and the filling of personal coffers. It was this venal and corrupt practice that led Luther to proclaim his 95 theses.

The technology then had intensified the corruption, but it was that same technology that was to spread the word of Luther’s protest and prime the pump of the Protestant reformation. This always seems to be the way with technological innovation. As much as it is a vector of negative disruption – corruption indeed – it is also the vector of progress and improvement. In 1450 there were no printed books in the world, by 1500 there were millions. Printing itself was and is morally and doctrinally neutral, without positive or negative valency per se: it could as well be used for the dissemination of official catholic propaganda (to use the Vatican’s own word) as it could be used for the transmission of what the church would consider subversive or heretical material. This held true over the centuries. Printing frustrated the church on the one hand – they had Diderot imprisoned for recruiting scholars and contributors to his great Encyclopédie, a project that attempted to describe the world in enlightenment and scientific terms – but on the other, printing allowed the propagation of printed bibles for missions around all the newly colonised corners of the world, spreading the power, reach and authority of the Holy See. It is worth remembering this point: the technology itself is neutral.

Gutenberg’s printing revolution, by way of Das Kapital and Mein Kampf, by way of smashed samizdat presses in pre-Revolutionary Russia, by way of The Origin of Species and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, by way of the rolling offset lithos of Fleet Street, Dickens, Joyce, J. K. Rowling, Mao’s Little Red Book and Hallmark greetings cards brought us to the world into which all of us were born, it brought us, amongst other things – quite literally – here to Hay-on-Wye. I started coming to this great festival before the word Kindle had a technological meaning, when an “e-book” might be a survey of 90s Rave drug Culture, or possibly an Ian McMillan glossary of Yorkshire Dialect.

Printed books haven’t gone away, indeed, we are most of us I suspect, pleased to learn how much they have come roaring back, in parallel with vinyl records and other instances of analogue refusal to die. But the difference between an ebook and a printed book is as nothing when set beside the influence of digital technology as a whole on the public weal, international polity and the destiny of our species. It has embedded itself in our lives with enormous speed. If you are not at the very least anxious about that, then perhaps you have not quite understood how dependent we are in every aspect of our lives – personal, professional, health, wealth, transport, nutrition, prosperity, mind, body and spirit.

The great Canadian Marshall McLuhan –– philosopher should one call him? – whose prophetic soul seems more and more amazing with each passing year, gave us the phrase the ‘Global Village’ to describe the post-printing age that he already saw coming back in the 1950s. Where the Printing Age had ‘fragmented the psyche’ as he put it, the Global Village – whose internal tensions exist in the paradoxical nature of the phrase itself: both Global and a village – this would tribalise us, he thought and actually regress us to a second oral age. Writing in 1962, before even ARPANET, the ancestor of the internet existed, this is how he forecasts the electronic age which he thinks will change human cognition and behaviour:-

“Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world will become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as in an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses go outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence. […] Terror is the normal state of any oral society, for in it everything affects everything all the time. […] In our long striving to recover for the Western world a unity of sensibility and of thought and feeling we have no more been prepared to accept the tribal consequences of such unity than we were ready for the fragmentation of the human psyche by print culture”.

Like much of McLuhan’s writing, densely packed with complex ideas as they are, this repays far more study and unpicking than would be appropriate here, but I think we might all agree that we have arrived at that “phase of panic terrors” he foresaw. Let me suggest a few of the anxieties we feel about the digital world today:

- Aside from the ugliness and ferocity of trolling on social media, we fret over the so-called post-truth age, with its arguments over what is ‘fake news’ and what are ‘alternative facts’ and the concomitant diminution of trust in any authoritative source of information, or consensus as to the validity and credibility of news and current events at all.

- The refusal of social media platforms to take responsibility for those dangerous, fake, defamatory, inflammatory and fake items whose effects would have legal consequences for traditional printed or broadcast media but which they can escape.

- The rise of big data and one’s personal footprint of analytics, spending and preferences, becoming, willy nilly, corporate property. The ever present threat to our privacy that this involves concerns us. Everyone we know, everything we read, watch, listen to, eat, everything we desire and perhaps every electronic message we send – all readable by a corporation or a government.

- The unfair non-contractual working practices afoot in the so-called Gig Economy – Uber Drivers, delivery couriers and so on. Not to mention the effect of those services on the pre-existing workforce of cab-drivers and others whose hard won qualifications might be set at nought.

- The ghettoisation of opinion and identity, known as the filter bubble, apportioning us narrow sources of information that accord with our pre-existing views, giving a whole new power to cognitive bias, entrenching us in our political and social beliefs, ever widening the canyon between us and those who disagree with us. And the more the canyon widens, the farther away the other side and the less likely we are to hear or see what goes on there, intensifying the problem and always at the super new speeds this digital new world confers.

- The threats to personal, national and transnational security – threats emanating from ‘bad actors’ that might be cyber-extortionists, unscrupulous corporations, unfriendly foreign powers, intrusive domestic governments and their agencies.

- The threat to the young of grooming that leads to abuse, or of recruitment that leads to extremist and violent ideologies and actions.

- Algorithms continue every microsecond to harvest data of my movements, by GPS for example, analyse my actions, read my gmail, build up information on my mood, sexuality, political, religious and cultural affiliations, habits and propensities – such data is for sale …

- Bullying – especially of the young. Body shaming. Blackmail. Extortion. Revenge porn. On-air suicides, encouragements to self-harm and live-streamed violence.

- The corporate assault on net neutrality.

- The fragile security of our entire digital world and the ever-present looming possibility of a Big One, that cataclysm brought about either by malice, act of war, systemic technical failure, or some other unforeseen cause, an extinction level event which will obliterate our title deeds, eliminate our personal records, annul our bank accounts and life savings, delete all the archives and accumulated data of our existences and create a kind of digital winter for humankind.

These are some of the things that rightly worry us. An example of every one of them can be found almost daily in a story on-line or in the mainstream so called dead tree media. All of them individually, or in a potential catastrophic avalanche, threaten to engulf us. One thesis I could immediately nail up to the tent flap is to join in the call for aggregating news entities like Facebook to be legally classified as publishers. At the moment they are evading responsibility for their content because they can claim to be ‘platforms’ rather than publishers. Given that they are the main source of news for over 80% of the population that is clearly an absurd anomaly. If they and Twitter and like platforms recognise their responsibility as publishers it will certainly help them better police their content for unacceptable libels, defamations, threats and other horrors that a free but legally bound press would as a matter of course be expected to control. But that correction of the legal standing and responsibility of social media platforms is almost certainly going to happen and soon, and is, frankly, small potatoes – as, to some extent, are the other anxieties I’ve outlined. For there is so more, so much more coming – as they say in America – down the pike. Some huge potatoes are looming on the horizon.

First, let’s just take time to remember how it all came about. I bought my first computer in 1982. We early adopters were like pioneer motorists in the first age of the internal combustion engine. You couldn’t feasibly drive a car without knowing how the engine worked. Every mile or so you had to, in the words of a popular song of the time, get out and get under your automobile, you had to tweak the magneto and adjust the carburettor and so on. And now? Now you never have to look at the engine from one year to another. All you have to know is how to negotiate the traffic. Just like computers and networking. No need now to know how to program, how to write an Interslip modem script or tweak your subnet mask. All you have to know is how to drive the thing such that you can get where you want to get safely and reliably. Now of course, with both cars and computer networking, the highways are clogged, one-way systems everywhere, streets are blocked, advertising hoardings deface the roadside, toll roads are in operation, car thieves patrol your area, speed traps, parking fees and towing away blights your life and traffic is a nightmare. Back then, ah the joys of the open road, you may have looked silly in your goggles and acoustic couplers, but what bliss it was in that dawn to be alive and to be young was very heaven. Just as when cars were slow, so when modems were slow, traffic was light and the illusion was of speed.

In the 1980s I joined Prestel and CIX, text based bulletin boards and information exchanges, then CompuServe an online service that allowed GIF in the 80s then finally Demon Internet allowing me to be a cybernaut. I literally did not know a single other human being who was on the net. I felt like the only person in Britain with a tennis racket. Not much chance of a game. But I got to know people from other countries as we swapped emails and techniques for getting in and out of university servers. There was no world wide web at this point. There were search engines like Veronica, JANET, WAIS, the Gopher project, telnet, irc, ftp etc etc. A world, as ever, of initials and acronyms. Commercial online services like CompuServe and AOL began to grow and offer their paid customers ‘ramps’ onto the true wild west of the internet. Then came Tim Berners Lee’s invention, the worldwide web and the arrival of the first browsers, Mosaic and then Netscape. It was the early days of portals, reliable feature-rich, for their time, home page gateways. Excite, Lycos, Prodigy, Alta Vista, Earthlink, Yahoo, Ask Jeeves were the big portal and search engine names. The rise of AOL seemed permanent and unstoppable. Every shop counter had piles of their introductory CDs, every glossy magazine had them taped to their cover. They were so big, they became the lead name in the giant media corporation they created, AOL Time Warner, which now embarrassedly hides the name AOL and pretends they don’t exist, from hot hot hot to icy cold in less than a decade. To have an AOL or hotmail email address is now so uncool it’s probably retro-cool again. In the mid-90s I did a film Wilde, first movie to end credits with a URL – if you watch the last screen says www.oscarwilde.com (since expired). That year an outfit called Google arrived with a fancy new set of search algorithms, Steve Jobs rejoined the company he had founded but from which he had been fired. The iMac arrived. Then came the new millennium and the fear of the year 2000’s millennium bug. Things hotted up. The iPod ‘disrupted’ to use that annoying word, the whole music industry. In 2005-6 Facebook opened up to the world, Ten years ago, almost to the week, the iPhone arrived. Twitter landed and various other social media services followed, Quora (for grownups), Snapchat (for children), Instagram (for the tragic) and so on. And here we are.

I’m sure you all remember the myth of Pandora’s Box. Which was really Pandora’s Jar. We call it Pandora’s Box because no less a figure than one of the heroes of early humanism, Erasmus, mistranslated it. The myth was told in Hesiod’s Works and Days, which described a pithos or jar. It seems Erasmus, when he translated it from the original Greek into Latin, mistook the word for pyxis meaning box, like the pyx in which priests to this day keep the communion host. So the jar became a box, showing that fake news could spread and replace the truth even before the days of printing.

Pandora and her jar were all part of Zeus’s revenge on Prometheus and us. He had not forgiven him for stealing fire from heaven and giving it to mankind. The gods had looked down and seen fires breaking out everywhere, industry, ceramics, cooking, foundries for art and war – but they saw the divine spark too, the creative fire that raised us to divine levels. Zeus was to punish Prometheus by chaining him to the Caucuses and sending eagles, or perhaps vultures, to peck out the immortal Titan’s liver every day. But mankind he punished in a more subtle way: and for once I use the word mankind without fear of being tutted. There were no women at this point. The god Hephaestus, Vulcan to the Romans, was commanded by Zeus to create the first human female from clay moistened by his spittle. Hephaestus took his wife Aphrodite, his mother Hera, his aunt Demeter and his sister Athena as models and lovingly sculpted a girl of quite marvellous beauty into whom Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty then breathed life.

The other gods joined together to equip her uniquely for the world. Athena trained her in household crafts, embroidery and weaving, and dressed her in a glorious silver robe. The Charites, or Graces, were put in charge of accessorising this with necklaces, broaches and bracelets of the finest pearl, agate, jasper and chalcedony. The Horai, the Hours, plaited flowers around her hair until she was so beautiful that all who saw her caught their breath. Hera endowed her with authority, poise and self-possession. Apollo taught her skill in music, learning, archery, rhetoric and reason. Hermes schooled her in the arts of deception, curiosity and cunning. And he gave her a name. Since each of the gods had conferred upon her a notable talent or accomplishment, she was to be called All-Gifted, which in Greek is Pandora.

Hephaestus bestowed one more gift upon this paragon, which Zeus presented to her himself. It was a jar/box filled with … he did not tell her.

Well you know what happened: after weeks of aching curiosity Pandora waited until she was alone in the house and – she couldn’t help herself, which of us could? She pulled the jar from its hiding place and twisted the lid. Its waxen seal gave way and she pulled it free. There was a fast fluttering, a furious flapping of wings and a wild wheeling and whirling in her ears. She cried out in pain and fright and jumped back as she felt something leathery, scaly and bony brush her neck, followed by a sharp and terrible prick of pain as some sting or bite pierced her skin. More and more flying forms buzzed from the mouth of the jar – a great cloud of them chattering, screaming and howling in her ears. With a cry Pandora summoned up the courage and strength to close the lid and seal the jar.

Like a cloud of locusts, the shrieking, wailing creatures flew away over the town, over the countryside and around the world, settling like a pestilence wherever humankind had habitation.

The names of the creatures were Ponos, Hardship. Limos, Starvation. Algos, Pain. Dysnomia, Anarchy. Pseudea, Lies. Neikea, Quarrels. Amphilogiai, Disputes. Makhai, Wars. Hysminai, Battles. Androktasiai and Phonoi, Manslaughters and Murders.

Illness, violence, deceit, misery, cruelty, lies and anarchy had arrived. They would never leave the earth.

What Pandora did not know was that when she shut the lid of the jar so hastily she forever imprisoned inside one last little creature , which was left behind to beat its wings hopelessly in the box for ever. Its name was Elpis, Hope.

The comparison seems rather good, don’t you think? If Gutenberg’s revolution was Pandora 2.0 and the Industrial Revolution 3.0 then the information age is Pandora 4.0.

When I first found out about and joined the internet and watched it grow with the arrival of the www I described it to friends, whom I was anxious to convert and get themselves email addresses, as the greatest gathering of human beings in the history of the planet. As new services came on line and web 2.0 blossomed into the social media services we now know and perhaps rely on, I believed, I really believed, that humankind might well be saved by the all-gifted net. It would spread, art, literature, music, culture, philosophy, enlightenment and knowledge. In its train would come new freedoms, a new understanding between the peoples of the world, a new contract. This was to be our millennium’s Pandora, an all-gifted organism that would bring nothing but learning, understanding, amity, comity and friendship. I looked at budding projects like Wikipedia and I saw Diderot’s enlightenment dream becoming a reality. I saw art galleries and archives becoming freely available to all. I saw special interest groups able to exchange information and ideas with their fellows across the globe: whether it was coin-collecting, a love of a particular style of music, a shared pleasure in gaming, hiking or cosplay, a rare physical or mental disorder in common – suddenly people could contact each other across the world. Free translations, free lectures, tours, user-generated advice on travel, hunting for the best deals and bargains, sharing experience in all fields of human endeavour. Borders, barriers, frontiers and boundaries would melt and dissolve. An end to tribalism, racism, ignorance and fear. A new dawn for mankind. It was all good. You are allowed to laugh at my naivety, I do myself.

And when Twitter, which I had joined early on thinking it a fun trivial little nonsense that might be worth pursuing, when it showed how people could connect in real time as they massed in the squares of Tunisia and Egypt ushering in the Arab Spring, my joy was complete. What tyrant could endure in this new world? How could censorship and propaganda survive when the wisdom and knowledge of crowds was there to shine the light of truth in all the world’s darkest places? This was paradise come to earth. Utopia made real! What could possibly go wrong?

When did I become aware, when did we start to notice that perhaps it wasn’t quite so perfect after all. Well, the odd caterpillar in the salad, or fly in the ointment shouldn’t put us off. But the beating of the leathery scaly wings of something worse fluttering from the jar couldn’t be ignored even by so perfectly gullible and optimistic a fool as me. The lid had been lifted and trolls were flying out, bullies, monstrously cruel and malicious thieves, extortionists, brigands, pirates, liars, con artists, predators and monsters. Hope was nowhere to be seen.

So have I gone from dewy-eyed, dopy and idiotic optimist to dead-eyed, despondent and despairing pessimist? Or perhaps I am doing no more than responding to a few political developments of late that I don’t like and which seem to have been powered by social media. If the Brexit vote and the American general election had gone the other way, would I and others of my stamp be wringing our hands at the state of the online world? Surely these anxieties are just the moaning of the sneering metropolitan coastal elite who have finally been pushed off their smug self-satisfied perches by the voice of the real people. We have lost. The people have spoken. The alt-right, the Trumpians and the Leave Campaign were just more social-network-savvy, smarter, better organised and now you feeble Social Justice Warriors are crying foul on the whole system?

Well, I hope I can convince you it isn’t that at all. I am a great believer in the Wheel of Fortune, not the prime-time American gameshow, but the Roman rota fortunae. It never stops turning. Most of us in the this room can remember when Clinton and Blair and their centre-left Third Way ruled the roost. They were at the very top of the wheel and now they’re at the bottom. President Trump is now at the top of the wheel, which means he and his kind must, by definition (according to this metaphor at least) be on the way down. Indeed, I think we can perceive that since his surprise ascent to the apex he is already starting to descend. We have passed Peak Trump and the rest of his story will dissolve into mere gossip, weird news, hilarity and eye-popping scandal as he cycles down into failed nullity, the fate of even the most distinguished politicians. Historical mulch on the floor of history.

So I hope you see that I am not suggesting that the internet and our digital world are in need of repair because this or that political grouping ebbs or flows, waxes or wanes. The fact is everything I have thus far spoken about, is to some extent old news.

You might remember that when I listed those anxieties we all share at the moment I added that there is more, much more “coming down the pike”? So, here’s my estimation of what it is that’s coming.

I’ll frame it with this memory of my friend Douglas Adams, now 16 years dead – if only he were in my place giving this talk, how much his insights into technology, art and society are needed. I remember he recalled a 1930s Wonder Book of Science that he found in his parents’ attic. It had come out around the time of the development of domestically available electric motors, a technological advance that we don’t think about these days for a very good reason, which I’ll come to. I’m talking about the development which would allow a motor to turn, just as a steam engine did, but without the fuel having to be in the house. The fuel was in the power station: the electricity came into your home and you could simply switch on an your motor. The Wonder Book showed what it imagined would be a Future House of the 1950s. In the attic they depicted a huge master motor with a great belt attached to a shaft from which ran other belts turning a clothes mangle for drying laundry, a washing-machine, a record-player – all kinds of devices magically imparted with mechanical motion thanks to the electric motor in the attic. Of course, the book suggested, householders of the future would have to be electric motor literate (though they didn’t use that exact phrase), able to maintain the motor, grease the shafts, apply belt-stick to the canvas of the belts to stop them slipping and so on. This book, with its cutaway illustrations and belts on shafts slapping and driving throughout the house looks comically absurd to us. But the authors were right, electric motors would go on to revolutionise our lives: what they failed to foresee is that we wouldn’t have to know a single thing about them. They would miniaturise and become embedded in our machines, self-regulating and invisible. They’re in our washing-machines, in our vacuum-cleaners, in our CD drives, smoothie-blenders, blu-rays, ovens, car windows, fridges, printers, coffee-makers a hundred thousand objects we use all the time but never think twice about. The electric motor became people literate. Fifty years after the wonder book we were all being told that we had to be computer literate, but no – just as with the electric motors, miniature computers appeared in our music players, our phones, ovens, cars, washing-machines, alarm clocks, phones, cameras, coffee-makers.

Well, you might have heard of IoT, the Internet of Things. Just as electric motors and computers began to be seamless, transparently, almost invisibly incorporated into every days objects that already existed and new ones that were developed for our convenience, so internet connection is being baked not only into todays electrical devices and appliances, but into ordinary domestic objects too. Things. Through radio protocols like wifi, Near Field Communication and Bluetooth everything from lightbulbs, door-locks, central heating thermostats, shopping lists, alarm systems, fridges, luggage, clothes, human bodies and bloodstreams that are constantly online, remotely available and controllable through web, smartphone and computer apps (I blush to confess I have – early adopter/idiot that I am – fallen for most of them, we have an internet connected fridge in our Los Angeles home and wherever I am in the world I can see inside it, thanks to its three cameras). Many of these IoT, Internet of Things objects, so called smart devices, are the classic example of a solution looking for a problem. I would include my fridge in that. But people in all walks of life are now investing hugely in this future: millions of IoT products are sold every month, you’re probably becoming more and more aware (if you haven’t already made the plunge) of Virtual Assistants, second generation advances on Alexa, Siri, Hello Google and the freakishly and inexplicably named Cortana. These, once installed, typically as speaker units in the home, in order to work, listen to every word spoken within auditory range. This makes these and all IoT devices, you will have realised quickly, a soft, ripe low-hanging target awaiting any hacker who can, if so disposed, link co-opted devices and use them as slave elements in giant bots, malicious automated cyber-dragons that combine the processing power of their enslaved devices to wreak enormous damage and stage spectacular data and currency heists.

Many of us who have shown an interest in the development of computing, watched over the years as two other nascent technologies struggled to match the almost supernatural properties of their popular science fiction manifestations. Robotics and artificial intelligence. The great Marvin Minsky, regarded by many as the father of Artificial Intelligence, knew that whatever kinds of AI were espoused – brute force, expert systems, machine learning, heuristics, genetic programming, neural nets – the reality, the successful system, would almost certainly be a mix of all those approaches. Above all, the success of AI was dependent upon reaping the advantages of the ineluctable Moore’s Law that has seen the year on year exponential increases in speeds and memory capacities necessary for the construction of workable AI. Gordon Moore, the founder of semiconductor company Intel, first proposed some time in the 1960s that processing speed/power/capacity would double every 18-24 months. What he actually said is that you would be able to place double the amount of transistors in the same square inch of silicon which amounts, broadly speaking, to increasing power and speed. This is the reason everything has sped up so extraordinarily. Pong, the monochrome tennis game with a slidey-up-and-down bat and a square ‘ball’ was not a result of inefficient, unimaginative, ignorant computer programming, it was the most you could do with chips as they were, the programmers were incredibly gifted and pushed the processor to its limit. Today’s 3D augmented and virtual reality graphics are no smarter really, they’ve just got a Maclaren to drive, not a Model T.

So it’s not just that computing power increases every eighteen months or so, it doubles. The speed, power and capacity from which it is now doubling boggles the mind and allows a whole new kind of technology to arise, or if you want to be Yeatsian and apocalyptic, to slouch towards Bethlehem to be born.

The almost metaphysical question of consciousness, feeling and the passing of the famous Turing Test aside, Moore’s Law’s delivery to developers of ever doubling processing speeds and capacity was always going to turn science fiction into science fact. It was never an ‘if’ or a ‘whether’, it was always a ‘when’. As far as cybernetics and robotics are concerned, there are different issues of moveable parts and sensory mechanisms. Moravec’s paradox comes in to force here, which states that computers are very good at what humans find difficult, but very bad at what we find easy. For example, machines can do lightning fast calculations and feats of memory way beyond human capacity, but no machine has been built that can approach the motor and perception ability of a one year old. Which, when you think about it, is just as it should be, we want machines to be good at the things we find hard and don’t need them to be good at the things we find easy.

Nonetheless, just as physics tries to unify fields of force, so technology unifies its different fields and the point is this:- the Internet of Things, Robotics and Artificial Intelligence are now essentially one and the same thing. In America I own a car that is capable of autonomous driving. I sit on the freeway, pull twice on a stalk on the steering wheel, fold my arms and tuck in my feet, the car, one of Elon Musk’s Tesla models, does it all – it brakes when the car approaches a vehicle up ahead and keeps an optimum distance. It speeds up when it can. It slows to a halt when it needs to and starts again. Thanks to GPS, it remembers where speed bumps are and raises the suspension the better to handle them. It even opens my garage doors automatically as I approach and closes them when I leave home. And this is nothing nothing compared to what is to come. The impact on our lives and employment is incalculable, just as the effect on the world of Tim Berners-Lee’s web protocols and programs http and HTML were incalculable. We are talking about nothing less than the mass obsolescence of much of the human workforce. Not mass unemployment necessarily but mass redeployment certainly. Not just in the sector that Americans call blue collar. Assembly lines have been replacing humans with machines for years. But white collar, college-educated workers are now being replaced too. Already an insurance company in Japan has installed an AI office system that replaces 60 clerical workers with just one whose role is to maintain the AI system. Trucks will be autonomous, ie driverless, very soon. And trains of course. Fun strikes ahead in the Southern Rail region. All this will happen in no longer than the length of time I’ve been coming here to Hay and have watched mobile phones become smart phones, watched AOL rise and fall.

Money is the great driver of course. The moment cars that self-drive are shown actuarily to have fewer accidents than human-driven cars, then insurance premiums will sky-rocket for those who choose to drive. Share holders will adore, as they always have, the idea of firing workers and replacing them with non-unionised systems that never pull a sickie or blow the whistle on dodgy corporate practices. It is worth pointing out that when United Airlines cabin crew seemed to beat up and throw off the plane a doctor and hit the headlines, accruing staggering negative publicity, the share-price barely wobbled. When rival American Airlines gave their staff a pay-rise, something that rarely rippled in the news cycle, their price immediately plummeted. The markets are a kind of artificial intelligence already, one that is not very human friendly, algorithmically led towards profit whatever the social cost. And clearly, worrying about the gig economy and the threat Uber drivers pose is almost comically dumb when Uber drivers themselves will be redundant in the very near future.

What else? Douglas Adams’s babel-fish, a real time language translation device, is not very far off. The day will come in our lifetimes when we will not be able to distinguish between pieces of music entirely composed by machine and entirely composed by humans. You might be familiar with the University of Oregon experiment in which pianist Winifred Kerner played three pieces, one by Bach, one by a computer program and one by a professor of music at the university called Dr Steve Larson. They thought the Larson piece was by a computer, the Bach piece was composed by Larson and that the piece written by the computer was genuine Johann Sebastian Bach. That experiment took place twenty years ago. It is very likely that your next absolute favourite hummable tune will be artificially written. Or poem. Or novel.

If intelligent systems can design systems more intelligent than themselves, the exponentially steep rate of improvement will dizzy our minds. It’s very important to keep this perhaps obvious point in mind: in the field of technology we never arrive at a state of finished satisfaction. The way things are now is not how they will be in two years time. Heraclitus said you cannot step into the same river twice, for fresh water is always flowing past you. The technological stream similarly allows for no sense of stasis. Technology is not a noun, it is a verb – a process. We know that our economics is in flux too, predicated and dependent on growth, growth, growth. What we have to accept is that there has been a confluence of that economic imperative for growth, Moore’s Law of ever-increasing computational power, human curiosity and ambition and our very particular kind of consumer addiction and need for the new – all of which have swollen the river of technological progress into flood.

Great gifts will come this new phase, from Pandora 5.0, of course they will. Let me sketch a few more or less at random and far from complete. History teaches that everything I say will be an underestimation. So, AI, robotics and smart devices in the biotech and medical sphere are already coming on line, the NHS has a deal with Google’s Deep Mind machine-learning AI (originally a British company Deep Mind is now the world champion at the game Go, which it taught itself), this kind of AI in the clinical realm will offer earlier diagnosis, the ability to read medical imaging data with much more accuracy and spot incipient signs of disease, making radiologists for example redundant; in the area of virology and related sciences it can assist with analysis of amino acids, protein structures and the creation of serums and treatments hugely accelerating drug development; we will see the manufacture of greater and better cybernetic prosthesis, bionic eyes, ears and limbs; more robotic surgery, faster and more accurate genetic analysis, genotyping and biometric data; brain computer interfaces, will allow thought and dream reading, the operation by thought alone of machinery, devices, musical instruments, paint brushes, tools; brain machine data input and output will transform a huge number of activities and operations allowing the happy combination (harnessing Moravec’s paradox) of the best human abilities of motor skills and perception with the best machine abilities of calculation and precision; we will see care robots for the elderly, cyber Mary Poppins guardians and babysitters for children and the vulnerable. The fight for greater longevity will unquestionably rely on AI techniques and usher in the possibility of the conquest of death itself. We are doubtless used to hearing that the first human to live to 200 years old is already alive, the younger people in this room can certainly expect to break the 120 barrier. I have been told by more than one solemn-faced scientist that the first person to live to 1,000 is probably alive and that immortality is technically and feasibly within reach. In other arenas, not counting the world of work, we will see better weather forecasting, an amelioration of traffic flow, automated shopping and delivery. A diminution of human error in multiple areas of exchange and interaction will lead to all kinds of undreamed of benefits.

The next big step for AI is the inevitable achievement of Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI, sometimes called ‘full artificial intelligence’ the point at which machines really do think like humans. In 2013, hundreds of experts were asked when they thought AGI may arise and the median prediction was they year 2040. After that the probability, most would say certain, is artificial super-intelligence and the possibility of reaching what is called the Technological Singularity – what computer pioneer John van Neumann described as the point “…beyond which humans affairs, as we know them, could not continue.” I don’t think I have to worry about that. Plenty of you in this tent have cause to, and your children beyond question will certainly know all about it. Unless of course the climate causes such havoc that we reach a Meteorological Singularity. Or the nuclear codes are penetrated by a self-teaching algorithm whose only purpose is to find a way to launch…

It’s clear that, while it is hard to calculate the cascade upon cascade of new developments and their positive effects, we already know the dire consequences and frightening scenarios that threaten to engulf us. We know them because science fiction writers and dystopians in all media have got there before us and laid the nightmare visions out. Their imaginations have seen it all coming. So whether you believe Ray Bradbury, George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Isaac Asimov, Margaret Atwood, Ridley Scott, Anthony Burgess, H. G. Wells, Stanley Kubrick, Kazuo Ishiguro, Philip K. Dick, William Gibson, John Wyndham, James Cameron, the Wachowski’s or the scores and scores of other authors and film-makers who have painted scenarios of chaos and doom, you can certainly believe that a great transformation of human society is under way, greater than Gutenberg’s revolution – greater I would submit than the Industrial Revolution (though clearly dependent on it) – the greatest change to our ways of living since we moved from hunting and gathering to settling down in farms, villages and seaports and started to trade and form civilisations. Whether it will alter the behaviour, cognition and identity of the individual in the same way it is certain to alter the behaviour, cognition and identity of the group, well that is a hard question to answer.

But believe me when I say that it is happening. To be frank it has happened. The unimaginably colossal sums of money that have flowed to the first two generations of Silicon Valley pioneers have filled their coffers, their war chests, and they are all investing in autonomous cars, biotech, the IoT, robotics Artificial Intelligence and their convergence. None more so than the outlier, the front-runner Mr Elon Musk whose neural link system is well worth your reading about online on the great waitbutwhy.com website. Its author Tim Urban is a paid consultant of Elon Musk’s so he has the advantage of knowing what he is writing about but the potential disadvantage of being parti pri and lacking in objectivity. Elon Musk made enough money from his part in the founding and running of PayPal to fund his manifold exploits. The Neuralink project joins his Tesla automobile company and subsidiary battery and solar power businesses, his Space X reusable spacecraft group, his OpenAI initiative and Hyperloop transport system. The 1950s and 60s Space Race was funded by sovereign governments, this race is funded by private equity, by the original investors in Google, Apple, Facebook and so on. Nation states and their agencies are not major players in this game, least of all poor old Britain. Even if our politicians were across this issue, and they absolutely are not, our votes would still be an irrelevance.

When Steve Jobs was asked the secret of his success he often liked to quote the great Canadian ice-hockey legend Wayne Gretzky who was asked why he was so far and away the greatest player of his, or perhaps any age. Gretzky’s reply was that while other players skated to the puck, he skated to where the puck was going to be. That what how Jobs saw as the necessary practice of the innovator. Business leaders and politicos always say with bland regularity that change brings as many opportunities as it brings challenges. The dark side of the rise of the machines, the sudden obsolescence of so many careers and jobs, the insecurity, the potential for crime, exploitation, extortion, repression, surveillance and even newer forms of cyberterrorism give us the collywobbles and suggest challenges for sure, but we must understand that it is going to happen collywobbles, initial resistance or not, because the lid is already off the jar, so the best we can do is keep it off and let hope fly out.

I do submit that it is nothing short of scandalous to be in the middle of a general election in 2017, on the very brink of this awe-inspiring, terrifying, scarcely credible but unquestionably real and imminent revolution, and find that politicians are skating not to where the puck is going to be, not even to where the puck is, but – as ever – to where the puck used to be. Westminster’s and the main political parties’ records on this subject are truly abysmal. Their ignorance and ostrich-like refusal to come to terms with the internet’s direction of travel has always been lax, ludicrous and laughable but it is also dangerously irresponsible. The state of the broadband infrastructure in rural areas is shambolic and contemptuous. As for the moaning about the expense and delays and subsequent abandonment of that aborted all new NHS IT system, well those chickens have come home to roost, haven’t they? The scandal of Britain’s largest entity, the NHS, using ancient Windows XP and even NT systems in 2017 with update and security patch costs not paid for. Wow.

The only manifesto commitment I can see on this subject is an unenforceable and irrelevant one that suggests a new Conservative government is going to attempt to increase its powers of control over Internet Service Providers, proposing to force ISPs to dislodge their users’ histories, there will no doubt more nagging to open up end-to-end messaging apps too, but it’s all skating to where the puck was.

But we are no good, any of us, at dealing with the future, politicians perhaps least of all thanks to a short electoral cycle and a race to the simplistic, unscientific and ill-informed bottom when it comes to the future. By way of example from another realm: Social Care is a hot button issue this electoral cycle, but everyone knew twenty years ago that the demographic inevitability of a population bulge going into retirement and old age having to be funded by a dwindling tax base was coming to pass and that is when plans should have been made, not now when it is almost too late and much, much more expensive and difficult. No one had the guts to say these things out loud at election time 20 years ago. Similarly, no one is talking now of the threat to employment, privacy, security and civil liberties of the remorseless, unstoppable convergence of the Internet of Things, Robotics and Artificial Intelligence or of the golden promise of that revolution. No one is suggesting how this will impinge on the education of the young and the re-education of the working population. The phenomenon of the ever expanding service industries we have relied on for so long is all very well, but you can have just so many Starbucks and Gregg’s on any given street and who is to say a robo-barista isn’t already being trialled somewhere in Seattle or the Santa Clara valley?

If you have children you should be encouraging them and their teachers to research into the careers of the future, some of which are very exciting. Social Robotics will be a big field for example, well worth looking that up – it’s a blend of social anthropology, psychology and design. Then again your son or daughter could be one of the first lawyers to specialise in Robot Rights, perhaps work on establishing charters for the building in of values and ethical systems or maybe they will go the other way and start up Robot Brothels catering to all tastes, because if history teaches us anything it’s that the sex industry will be coining it before any minister of state works out what’s going on.

So one thesis I would have to nail up to the tent is to clamour for government to bring all this deeper into schools and colleges. The subject of the next technological wave, I mean, not pornography and prostitution. Get people working at the leading edge of AI and robotics to come into the classrooms. But more importantly listen to them – even if what they say is unpalatable, our masters must have the intellectual courage and honesty to say if they don’t understand and ask for repetition and clarification. This time, in other words, we mustn’t let the wave engulf us, we must ride its crest. It’s not quite too late to re-gear governmental and educational planning and thinking.

You could argue convincingly I think that one of Churchill’s greatest qualities, one which helped turn the tide of the Second World War, was his openness to science and technological development, as shown in the Science Museum exhibition a couple of years ago dedicated to his role in that sphere. The development of radar, which he supported, was of course a vital part of the victory in the skies in 1940. Sonar too was of incalculable importance in the Battle of the Atlantic. Churchill always listened to his adviser Lord Cherwell, whom he called the scientific lobe of his brain, he got behind wonderful inventions and developments like the Bouncing Bomb, Operation Windows and gyroscopes, and of course that famous five word note he sent concerning the money going into the decryption developments in Dollis Hill and Bletchley. A Treasury official queried the amounts. Churchill visited the Research Station and saw the Colossus vacuum tube computer and its Mark 2 version under construction, he listened, he absorbed and pondered. when he returned to Downing Street he scribbled a message to the Treasury. “Give them what they want,” he wrote. That short note could be regarded as one of the founding documents of digital computing. Of course, you could justly observe that Hitler exhibited a like belief in science and the power of technology: prompting Churchill himself in one of his best known speeches to say: “… if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science…’” And perverted or not we all benefited from the inventions and technology that emerged from Germany under Nazi rule, from tape recording to rockets. I said earlier that printing was capable of being perverted into Mein Kampf or The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, into ransomware or fake news that incites murder. I can’t emphasise this point enough. Technology or science do not in and of themselves have moral valency. But at the moment we are blaming the technology rather than our lack of preparedness or understanding, which as Marshall McLuhan observed, is as witless as “… cussing a buzz-saw for lopping off fingers and complaining, ‘but I never saw that coming’.”

The witlessness of our leaders and of ourselves is indeed a problem. The real danger surely is not technology but technophobic Canute-ism, a belief that we can control, change or stem the technological tide instead of understanding that we need to learn how to harness it. Driving cars is dangerous, but we developed driving lesson requirements, traffic controls, seat-belts, maintenance protocols, proximity sensors, emission standards – all kinds of ways of mitigating the danger so as not to deny ourselves the life-changing benefits of motoring.

We understand why angry Ned Ludd destroyed the weaving machines that were threatening his occupation (Luddites were prophetic in their way, it was weaving machines that first used the punched cards on which computers relied right up to the 1970s). We understand too why French workers took their clogs, their sabots as they were called, and threw them into the machinery to jam it up, giving us the word sabotage. But we know that they were in the end, if you’ll pardon the phrase, pissing into the wind. No technology has ever been stopped.

So what is the thesis I am nailing up? Well, there is no authority for me to protest to, no equivalent of Pope Leo X for it to be delivered to, and I am certainly no Martin Luther. The only thesis I can think worth nailing up is absurdly simple. It is a cry as much from the heart as from the head and it is just one word – Prepare. We have an advantage over our hunter gatherer and farming ancestors, for whether it is Winter that is coming, or a new Spring, is entirely in our hands, so long as we prepare.

I can at least, unlike Martin Luther, thank you for your indulgence.

Thank you.

Stephen Fry