Passions

Blogging down one’s thoughts can sometimes end in bogging them down. Political events, ideological disagreements, rants, apologies, defensive screeds and coverage of techno launches, political scandals and general media excitements have often been the meat, drink, potatoes, peanuts and popcorn of my blogging space, which is fine and well and high and dandy and adorable in its own way (one hopes) but it leaves little time for dilating on the subjects which really move and enliven me. So here is the first of a series of blogulosities in which I try and share a personal delight.

I shall begin with a passion that has been with me since … well, since I was young enough to look and wonder I suppose. Like many of my generation I was made a prisoner for life from an early age by the remarkable Ernst Gombrich, whose The Story of Art Pocket Edition is probably responsible for opening more eyes to painting and sculpture than any other book published in the English language. If you aren’t familiar with it, I am not sure there is any work I could recommend more highly. If you are on a Gombrich spree you might like also to get hold of his A Little History of the World, which will make you and any children you have handy writhe, ripple and froth with pleasure.

Since reading The Story of Art I have loved looking at pictures. At school I took History of Art (or ‘history o fart’ as I would write on my exercise books because I was exceedingly sophisticated and amusing) for A level and did seriously consider the subject for a degree either at one of the universities or perhaps the Courtauld Institute. The Courtauld, if you don’t know it, has a spectacular and woefully undersung gallery at Somerset House in London, which houses stunning impressionist and post-impressionist paintings, as well as owning perhaps the best art image collection in the world, the Witt Library.

When I was seventeen, on the run from the police and in possession of someone else’s credit cards (don’t ask, you’ll have to read Moab is My Washpot or The Fry Chronicles to know more. Many sensible people acquire both books and find that good luck and bedroom success attends them for ever afterwards. That may be a coincidence, but it seems unlikely) I would, pompous twazzock that I was, perch myself on a barstool in the American Bar of the Ritz Hotel and converse with the barman there, who happened to be an enthusiastic and highly knowledgeable amateur art historian. His bible was the three volume The economics of taste: The rise and fall of picture prices, 1760-1960 by Gerald Reitlinger and he would mix my Old Fashioneds, show me slides of paintings (he kept an enormous collection under the bar counter along with his maraschino cherries, orgeat and swizzle sticks) and preach the gospel of Reitlinger.

Looking at pictures

To stand in front of an artwork can cause bursts of excitement and surges of pleasure and thumps of intense feeling that are not unlike those an adolescent experiences when glimpsing someone who stirs desire in them. It pleases me that every year more and more people go into art galleries and museums to look at collections or special exhibitions. All over the country we are spectacularly blessed. Places that show photographs, sculptures, decorative objects, textiles, porcelain and paintings exist in almost every major town and city in Britain. Many are free and almost all offer good discounts for those who most need them.

For any of you plagued by memories of having to troop listlessly after your parents or school group leader as you were shepherded from one masterpiece to another and forced to listen to well-meaning but often confusing, stultifying or irrelevant explanations and interpretations from tour-guides and experts, I have nothing but sympathy. We have all been there. If that has put you off galleries and exhibitions in later life then you have the unimaginable pleasure ahead of discovering what it is like to look at pictures in your own time, at your own speed, just as you please. The beauty of art galleries when you are no longer in a tourist group or family is that you don’t have to go “round” – you can pop in to see just one room, or even just one painting. There are no rules and no “correct” way to look.

In a speech for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, which I published as a blog a month or so back, I talked about how deeply embarrassing and unsettling the whole business of confronting an artwork can be. How do we respond? What are we meant to know? Suppose there are such things as taste and judgment or necessary knowledge that other people have but I (or so I tell myself) don’t? Who is more pretentious, the one who praises the strange, the modern and the difficult or the one who loudly condemns them to show that he, for one, isn’t “fooled”? How can we rid ourselves of the kinds of self-consciousness that make us ask such silly questions in the first place?

We have all experienced embarrassment, self-consciousness and anxiety when looking at a piece of art. The word “art” is so overloaded anyway, burdened as it is with the highest metaphysical, aesthetic, cultural and social meanings over and above the general meaning of “paintings and sculptures and whatnot”. Few words, when given a capital letter, become so tendentious and vexing as Art.

I don’t want to overstate the “problem” of gallery visiting. We should forget all that and think of the pleasure that is to be had, the pleasure in feeding the eyes and brain with the colour and mass and weight, the emotional drama, wit and narrative, the excitement and the sheer beauty that only artists can offer. The first duty to art that we have is to trust our own responses. We should remember the suggestion Alan Bennett had that over the doorway of a great gallery should be written the words, “You don’t have to like everything…”

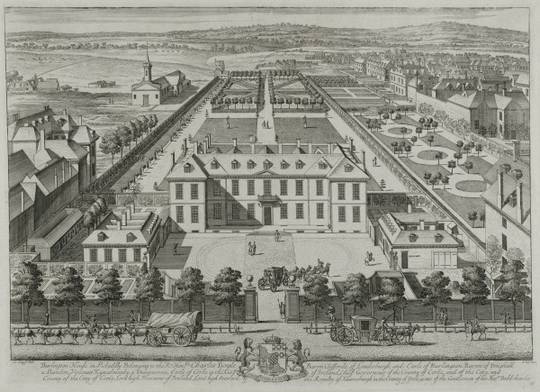

Two years ago I was touched and flattered to be asked to join the board of trustees of the Royal Academy, which has long been one of my very favourite places on earth to visit. Do you know it? The Academy was founded in 1768 and moved into Burlington House, its current Palladian home, about a hundred years after that. You enter a gateway on the north side of Piccadilly and a courtyard opens up, focussing on a central statue of the Academy’s founding president Joshua Reynolds, palette and brush in hand, although it is likely these days that the area will be dominated by whichever current exterior contemporary installation might be surrounding the old boy. You pass up some steps and into perhaps the most elegant and impressive viewing galleries and exhibition spaces in London.

What do I love about the RA? Well, the name is a clue. It is an academy. It is owned and run and governed, not by us trustees, but by the painters, sculptors and architects who make up its membership, from Gary Hume to Elizabeth Blackadder, from David Hockney to Tracy Emin, from Anish Kapoor to Norman Foster. But it is a true academy too: the RA Schools is the oldest art school in the country. Turner, Constable and Blake were taught there.

By virtue of its nature the Academy will always and by definition engage with, display and promote the works of living artists, but because it has the best rooms in the world and an unrivalled history of putting together exhibitions it will always be a place to come and see some of the most exquisite and extraordinary art objects the world can offer – in recent years previously unseen treasures from China, Turkey, Russia, the Middle East and, at the time of writing, Hungary. As it happens the Academy also owns and displays the only Michelangelo sculpture in Britain, alone worth the hundred yard walk from Piccadilly tube station… It’s called the Taddei Tondo, and is a kind of carved circular tablet of marble depicting the Madonna, the baby Jesus and the infant John the Baptist. It will make your heart skip a beat to think that someone can make such a thing armed with nothing more than a chisel…

Be a Friend

The Royal Academy is entirely independent, receiving not a penny of government funding. Much of its income is derived from its pioneering and hugely successful Friend’s scheme. I do not think there is a more pleasurable or fulfilling thing to be than a friend of the Royal Academy. Part of my purpose in writing this blog is to urge you to think of becoming one yourself, if you aren’t already. You can follow @royalacademy here on Twitter.

A Friend can go free and as many times as they want to any RA exhibition. They are invited to the exclusive previews, they receive a quarterly magazine and have access to the Friends’ Rooms, specially set aside places where you can sit and sip and be calm and collected right in the heart of London.

When the heart-stoppingly astonishing Anish Kapoor exhibition was wowing record crowds last year many people became Friends just in order to beat the queues and because they wanted to go again and again, taking friends and family along with them. I think the same will happen when the forthcoming Degas and Hockney exhibitions open.

If you feel that materialistic Christmas presents have become a bore: more plastic and packaging, more meaningless “luxury goods”, more trivial nonsense and senseless frippery, then you cannot imagine, in my opinion, of a better gift this year than a Friendship of the Royal Academy. Whether the lucky recipient of your present pops in for an hour when next in London’s West End or whether they make a special day of it, there really is no finer thing to have in your wallet or purse than a Friend’s card.

In case you think this is coming across as a heavy sell… well, it is. I am passionate about the Royal Academy and think it stands for all the very best in British cultural life. Goodness knows I love dozens and dozens of other museums and galleries too, but I believe that there is something special about the RA and I hope you will too. There is nowhere else like it on earth and, like so many great national institutions, it is perhaps undercelebrated. If you want to give the gift of academy friendship, all the details are here.

As a trustee I leave the true art expertise to the academicians and to Chief Executive Charles Saumarez Smith and his team. As for matters fiscal, financial and fiduciary – with these I am not to be trusted. I have never learned the trick of being able to read accounts. My eyes swim and all intelligence and cognitive ability deserts me. But if I can persuade any of you who are good enough to follow me to befriend this wonderful institution then I have done you a favour and at the same time helped a place I love to continue in its marvellous work.

x Stephen